#3 This Academic Life: On cherishing the mornings

Since my PhD I've always been an early riser, but in recent years this had become a ritual of resignation rather than the underpinning to creativity, and a fulfilling working practice.

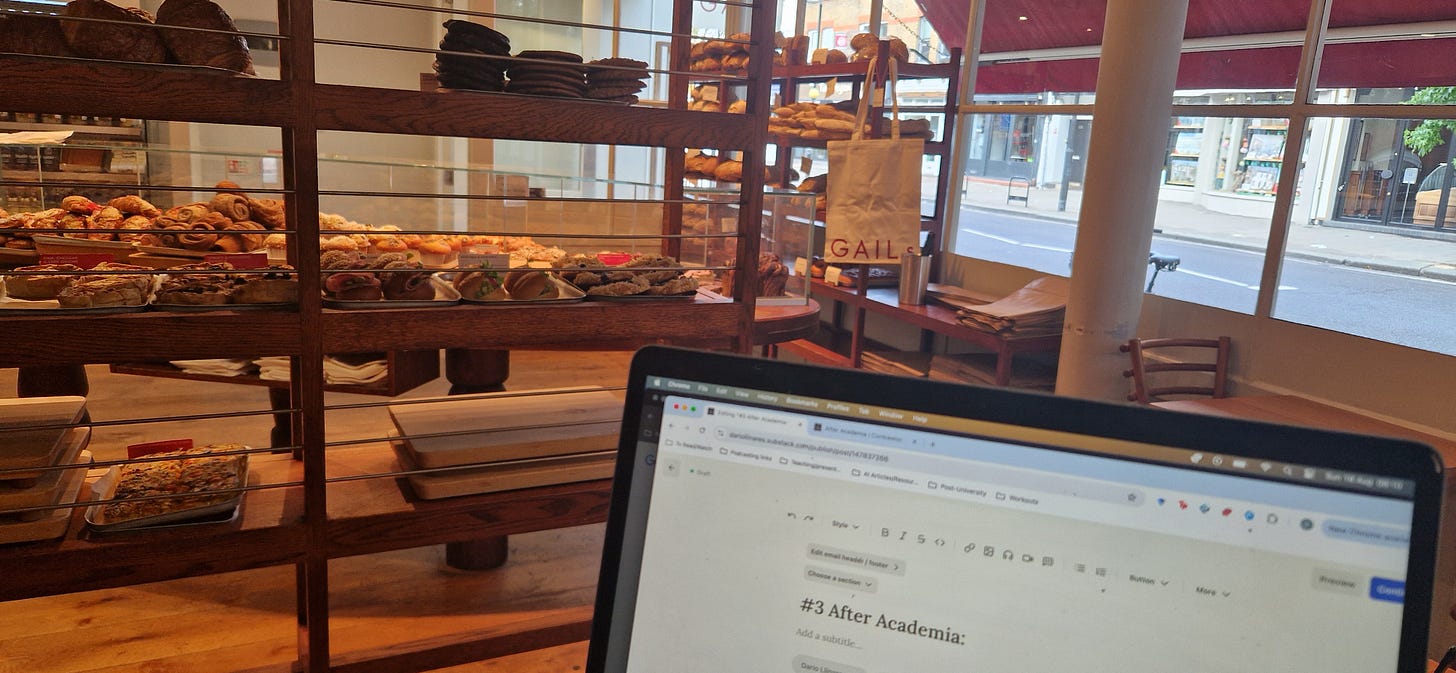

It’s 7 a.m. on Sunday morning, and I’m seated in my regular spot at Gail’s Bakery on Upper Street in Islington. I frequent this haunt because it opens every day at 7 a.m., and this corner stool is tucked away, yet it faces both the window and the counter. My father, whose questionable sagacity often seemed to derive from The Godfather films, used to say, “Always sit with your back to the wall; then you can see them coming.” Who exactly he meant, I never could ascertain. But I do like this spot where I can work and observe the comings and goings of the London metropolitan elite.

One of the drawbacks of working from home is the ingrained feeling of needing to move from one place to another as a kind of cue to start work. Years of commuting various distances seem to have imbued me with an internalised resistance to the journey from bed, via shower, to desk. Often, I’ll go for an early walk or run, which can be enough to make me feel like my brain and body are in sync. For writing, or any work that requires entering a deeply creative space, I seem to need that physical impetus. More than that, I need a sense of being in the world to galvanise some momentum.

In all honesty, the coffee isn’t even that good here, and there’s the added “problem” of confronting the pastries, lined up as they are like a Napoleonic army of complex carbohydrates. But I’m prepared to pay £4 for an Americano if it usually produces solid productivity before 9 a.m.

The air was still and thick as I walked the ten minutes from my flat, encountering just the vaping dog walker being pulled along by a magnificent golden Labrador. I like the idea of having a dog. After looking after friends’ dogs, Bailey and Zuuk, now and then, I can see the attraction—a pure form of companionship, reciprocal unconditional care, along with having a running partner who doesn’t get tired. But for decisions like this, the unknowns always freak me out. How did I ever manage to quit my academic job?

I promised myself this week’s writing would be shorter. Substack told me my last entry required 22 minutes of reading time. Is that too much to ask? Does it even matter? In my mind, the point of this writing is for it to be authentic first, embracing experimentation, imperfection, and even failure (whatever that means) as inherent to the process. Concerns of an imagined reader or the pragmatics of audience growth aren’t part of the equation. But I need to get better at that mindset.

Early Sunday morning in London. Late August. It’s beautifully ethereal. I know I’m in a different headspace now that I’m out of academia. I’m starting once again to think of the potential of the morning as the night before winds down. The heaviness of stress, or outright dread, has subsided. Yet I don’t feel strange, not having to worry all that comes with a new semester.

I often think about how much my PhD period reconfigured my identity—not just in what one might ostentatiously call psychological terms, but also in more practical, embodied ways. It turned me from a night person into a morning person, and from someone with a fundamentally lazy nature into, well, someone neurotically programmed for planning, organising, essentially disciplining myself toward the doing of things.

I find it near impossible to just sit and laze in bed, letting thoughts come and go. My inner voice is insistent. Thoughts are definitely not like drifting clouds that I can effortlessly let go of. I’m a catastrophiser.

The various meditation apps I’ve used always begin with some variation of this metaphor. The performative tranquility of a guiding voice entreats you to notice your thoughts, observe them like clouds, and let them disappear. It’s much easier said than done, particularly when your inner voice has the register of a yappy Dachshund, impatient to attack the world with its bijou self-importance. Lots of dog metaphors today for some reason.

Now, of course, getting up early is seen as a life-hack—one of the first principles of the productivity gurus who are everywhere these days. Be careful what you feed into the algorithm.

The romantic narrative I’ve concocted defines my early rising as a Zen practice.

I use the audiobook of Don’t Worry by Shunmyo Masuno as a soothing, somnambulant aid to sleep. (I’d also recommend Zen: The Art of Simple Living by the same author.) Chapter 12 in this book of crisp enlightenments is entitled “Cherish the Morning.”

I would like to talk about making use of your time rather than being used up by it. To be sound in mind and body—or better yet, to live vigorously—it’s important not to upset the rhythm of your days. If the time you get up in the morning and go to bed at night is constantly shifting from one day to the next, you cannot maintain optimal health, nor can you endure the mental exhaustion it causes. What’s more, human nature tends toward laziness. We can be as lazy as we set our minds to being. If we give in to laziness, there’s no end to it, and things only get worse. It’s necessary to put a stop to it at some point. What if you were to create your own rules to maintain your daily rhythm? It’s worth paying attention to your morning routine. Cherish the morning—I cannot emphasise this enough. Among the rules for cherishing the morning, the most important one to take to heart is to rise early at the same time every day. By rising early, you’ll create space in your morning.

This notion of the rhythm of routines is, without a doubt, the best way I have found to function. But it’s something you have to define and cultivate for yourself. It doesn’t just present itself, nor do we, as modern humans, have the ability to fend off the millions of distractions, nudges, and crises. One of the issues I faced in academia was that mornings were often given over to catching up on the day before. I found it difficult to block off that time for what Cal Newport calls “Deep Work” (another book worth reading). I don’t want to go off on a productivity tangent here, but the cultivation of one’s work processes is an art in itself. It requires both pragmatic systems that you put in place and the psychological discipline to follow them.

For me, the morning is vital because it sets the pattern for the day.

Still, I’m aware of the nagging critique that most people reading this might be thinking, That’s all well and good if you’re a Zen monk or a childless ex-academic with no job to go to.

As if no one had ever thought of it before—getting out of bed a bit earlier. Or those millions of “unseen” workers who keep the cogs turning aren’t already up at the crack of dawn because they have to be. Or the parents with infants, for whom late nights and early mornings have no fundamental distinction.

All of these Eastern philosophies, appropriated by decadent narcissistic Westerners, reflect a privilege that ignores the realities of modern life for most people.

Yeah, I get it.

But I still think the principle stands. I guess the trick is adapting it as best as one can to personal circumstances. Without tripping over my own pretentiousness, it’s the intentionality that matters.

In recent years, getting up early became too much a kind of fatalistic self-disciplining. Configured in my mind as a matter of imperative. An necessity asserted by the over-whelming needs of the large university degree I was running? It became something I had inure myself to. I became a something of a zombie, a drone, using social media, and podcasts to distract myself on the commute, resigned to the inevitable onslaught of emails.

My penchant for early rising started during my first summer working in Falmouth. I wanted to work on research projects that largely get shelved during term time. I used to be up at 6 a.m., walking or cycling from Falmouth town along the picture-postcard estuary front, up through the winding road of Penryn to the university campus. If the sun was out, casting long shadows across the grassy water, the walk to work infused me with a sense of aliveness. Whenever I go back to Falmouth, I always take that stroll again.

These thoughts about mornings in Falmouth were triggered by a notification that popped up on my Facebook feed. I still peruse that digital ruin largely just to keep up with friends and family. It also brought to mind the cyclical nature of our subjectivity when it comes to working lives. Back in the summer of 2015, I had been working at Falmouth for four years and was ready for a change. The move up to the University of Brighton was a career step up—more money, responsibility, credentials etc.

The tone of this short post (below) evokes someone who feels a sense of gratitude and optimism. Someone still very much aligned with and motivated by academia in its institutional form. Yet, in hindsight, maybe it was this move that sowed the seeds of the current context. I was searching for a version of working life that I wanted and believed I would find, still within the context of academia.

I wonder what purpose Facebook thinks these kinds of reminders serve. It’s strange how these random nudges are like external synapses, with the network firing them off without any concern for the ripple effects. Our algorithmic overlords, blurting out their own random memories, to which we are merely tangentially connected. It’s only our lives, after all.

My logical brain is trying to make connections between these initial musings about waking up early and what I wrote last week about "academic identity."

I was actually considering diving into the weeds on the subject of workload. If anyone is interested in a detailed polemic on things like teaching loads, a breakdown of marking and moderation hours, or perhaps a philosophical deconstruction of academia’s adoption of "Work Allocation Models," I can write about that. But it’s the broader concept of work that interests me more.

I’ve already gone on too long when I promised I wouldn’t. So, I’ll save this for next week: How do I define “work” in a new way? I’m undoubtedly caught in the narrative of two extremes—work as a fundamental part of identity, with value beyond economic imperatives, versus work as something overly instrumentalised, where many of us can’t see ourselves outside of it.

Since beginning this hiatus/transition, the mornings—a time and space for thought and “work” in a more creative sense—have started to return to me. They’re no longer a period of cognitive self-defense.

It’s getting busier in here now. Delivery drivers have been in and out. Is ordering a couple of croissants for takeaway at 7:30 a.m. on a Sunday morning an indulgence bordering on the profane? Who can say? Maybe it’s part of their Zen-inspired morning ritual.