#7 This Academic Life: Navigating the Conundrums of AI Creativity

Screening my video-essay - Do You Want to Hear It Talk? - to students, provoked something of a real-time working through of my ambivalent thoughts on using so-called AI.

In the past few weeks, I’ve ventured back into the university environment—visiting two institutions—to show a video essay I’ve been working on for the last six months. First, I took the trip from Paddington down to Cornwall, a serene, scenic journey (if the trains run smoothly), to Falmouth University, where some 14 years again I accepted my first full-time academic position. Roaming familiar spots on campus gave me an odd sense of both familiarity and dislocation; the cognitive map I carried only partially aligned with the reality of being back in these spaces.

Then, last week, it was north to Staffordshire University, where I was invited by Agata Lulkowska to speak with her filmmaking students. The campus, with its mix of shiny new buildings and rundown brutalist architecture, seemed to be grappling with its own identity, caught between regeneration and a lingering industrial past.

While I wasn’t nervous about standing in front of students again, I felt curious. How would students, immersed in traditional filmmaking, react to a piece that uses AI in its production? I was also eager to see my work in the stark setting of the auditorium, where any flaws would be unmistakable. My film currently runs at 42 minutes—long for an essayistic film—so I was open to critiques that might help with a final edit. In both sessions, I provided a brief introduction before showing the film, followed by a Q&A. Although it wasn’t quite finished, I’d reached a point where it felt coherent enough to present. Experiencing the vulnerability of being on the creator side of the creator/critic binary was eye-opening—a glimpse into the apprehension any artist might feel putting their work out into the world.

It’s easy to say, as many seasoned creators do, “I made the work for myself,” suggesting that audience response is of little consequence. Yet, when sharing a piece with an audience, there’s always a sense of wanting it to “connect” or “work” on its own terms. This video essay’s specific use of AI software was a point I anticipated would spark conversation.

Ambivalent Rationales and AI Filmmaking

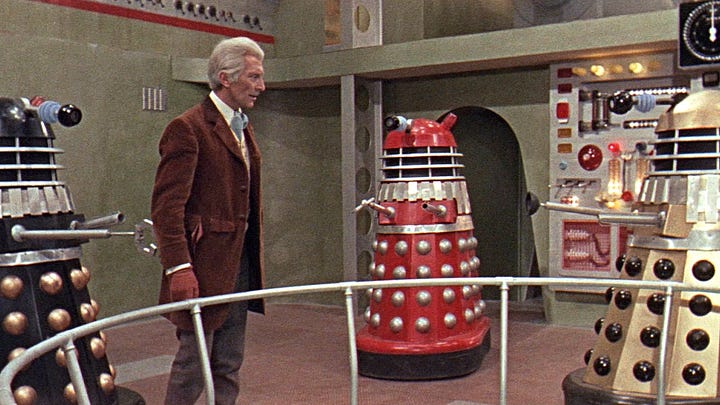

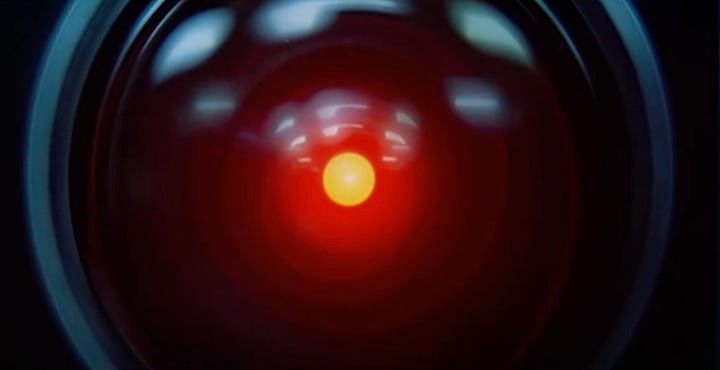

Do you want to hear it talk? explores the representation of speaking machines in science fiction cinema. Through clips from iconic voices—HAL 9000, the Daleks, The Terminator, Robocop, Chappie, and many more—the film examines how synthesised speech shapes and deepens the thematic and narrative fabric of sci-fi speculation.

The film also examines how recent advancements in voice recognition and artificial intelligence—technologies that have rapidly evolved over the past 5-10 years—have “caught up” with depictions of human-machine interactions in science fiction. Spike Jonze’s Her is a focal point in the latter half of the film, exploring the implications of a society where synthetic voices converse as naturally as humans. Voice recognition and synthesised speech, now underpinned by AI, have made the sonic interfaces of Her, released in 2014, feel even more prescient as time has passed.

As I worked on the film, I found myself grappling with ambivalence toward AI’s practical and ethical impacts on human experience. I say “so-called” AI because it’s both a technical and philosophical question as to whether these technologies actually constitute intelligence, especially in the context of artificial general intelligence (AGI).

I’ve always been drawn to the relationship between form and content in film—work in which aesthetic choices enrich theme, character, or narrative. This concept shaped my decision to create a narrator with a synthesised yet “human-sounding” voice, imagining an intelligence from a post-human future where machines and humans are fully integrated. This AI narrator adds an implicit meta-commentary: a synthetic voice examining the symbolism of synthetic voices as the bridge between humans and machines.

Throughout the process, I wanted to avoid presenting the film as an endorsement of AI as an inevitable path for audiovisual media. Instead, through a self-referential construction—applying both utopian and dystopian perspectives with an ironic touch—I aimed to underscore the tension between the possibilities and pitfalls this technology brings.

Navigating the Polemics

Entering the post-screening Q&A with my own stance on AI unresolved was an unusual experience. Reflecting on whether the film “works” independently, I wondered if my ambivalence toward AI would resonate with the audience—especially with students learning traditional filmmaking, who might be more resistant or confrontational toward new technologies.

Like most, my understanding of AI has largely developed through media narratives, which seem increasingly driven by polarised debates. I still have access to academic networks and forums, where research into AI’s expanding impact is being debated across various fields. In those spaces, I find a hope—perhaps naïve—for knowledge production that aspires to be non-ideologically aligned, exploring AI’s possibilities and limits with a critical yet open perspective.

Interestingly, my social media algorithms have inadvertently created opposing echo chambers. LinkedIn generally feeds me a steady stream of pro-AI posts, as I follow educators, researchers, and creators who are optimistic about AI’s potential. Meanwhile, my timeline on X predominantly shows a much more critical perspective, often with angry, absolutist invectives about the moral emptiness of AI or the apocalyptic path it might lead us down.

The sessions became a testing ground for both my own and the audience’s reservations—not only about AI in filmmaking but about its broader implications for society and human experience. They served as a real-time exploration of my own cognitive dissonance surrounding AI.

Below are a few interrelated points of dialectical tension that I’ve continued to ruminate on in light of these conversations—tensions that, if I’m honest, are unlikely to resolve anytime soon as I work to finish the film and seek more venues and contexts for screenings.

Resistance is Futile?

In both sessions, students were curious about the technical process of using AI software, which led, understandably, to broader discussions on AI’s impact on filmmaking. This is, of course, an impossible question to answer fully. Conversations with colleagues in cinematography and visual effects, recent news stories like Tyler Perry pausing a studio build, and the ongoing SAG-AFTRA strike—where AI use has been a key issue—highlight just how deeply AI is already affecting the industry.

Amid these discussions, I also sensed a general anxiety about a future that feels increasingly uncertain and abstract. I feel it myself at fifty, so I imagine it’s even more pronounced for those in their twenties. After one screening, a student spoke to me with an air of tired resignation, saying that AI is simply another force he’ll have no choice but to contend with.

This sense of inevitability is largely driven by corporate tech giants, who seem to respond to every social and ethical concern with “more technology” as the solution. The “move fast and break things” ethos—most famously championed by Zuckerberg—captures this approach: if we can do it, we will. It’s a mindset that leaves little room for philosophical reflection, let alone caution, regarding the societal repercussions of unchecked technological advancement.

How, then, does one weigh the positives and negatives of technologies that shape us as much as we shape them? Some students voiced outright refusal to engage with AI—a stance that has valid reasons, even if its feasibility varies.

In making this AI-infused film, I sought to embed these contradictions within the film’s structure, mirroring the tension of a technological future where creativity, education, politics, and social life are increasingly underpinned by social anxiety.

AI’s potential to streamline post-production, generate effects, and even assist in scriptwriting has undeniable appeal, particularly for independent filmmakers or students without access to high-budget resources. Yet efficiency is not an ethos that should be unquestioningly aligned with creativity.

For someone like me, who works independently, with limited budgets and without editorial oversight, AI offers enticing possibilities for audio-visual design that would otherwise be impractical or too costly. Yet, the skills that creative experts develop across all areas of production and post-production form the backbone of an industry where people both make a living and drive the art form forward.

With AI, I’m reminded of a scene in Moneyball where Brad Pitt’s character tells a disgruntled baseball scout, who realises he’s become obsolete in the new era of data-driven player analysis, to “adapt or die.” This mantra is both fatalistic and realistic. I certainly have significant reservations, especially about the “tech-bro” culture driving much of this innovation, not to mention the alignment of political regimes with these technologies. If I veer too far into the Trump/Musk axis, this article could go on endlessly.

Adapting doesn’t necessarily mean passively accepting AI’s influence; it means actively shaping the role of this technology in our lives. Without being too grandiose, creating work that critically engages with the ethics and implications of our actions—even using tools originally designed for passivity or control as a form of resistance—reflects the very reason we make art.

Learning How to Learn

In one of the key films explored in my video essay, John Badham’s 1983 Cold War techno-thriller Wargames, the protagonist David (Matthew Broderick) explains to his friend Jennifer the distinctiveness of the AI system he’s discovered, which was based on learning strategies in gameplay. At one point, he remarks that the machine “learns how to learn, so it would be better the next time they played.”

This line not only foreshadows machine-learning developments over the past thirty years but also hints at the evolving complexity of “learning” itself, particularly as it relates to the intelligence machines now exhibit. (If you haven’t yet, see AlphaGo for a fascinating look at game-playing AI—link in references.)

Learning is, of course, a loaded term. Does simply replicating an observed task constitute learning, or is it merely rote repetition? Human learning goes beyond imitation; it involves understanding underlying concepts, recognising patterns (yes, as in machine learning and large language models), but also connecting and applying ideas through abstraction and symbolic reasoning.

Humans synthesise diverse information, apply it to new contexts, and innovate. This “learning how to learn” is not merely about repetition but about building frameworks that enable us to adapt and transform knowledge creatively. It always amuses me when someone says, “I can’t remember anything I was taught in school.” The specifics may have faded, but school taught systems and practices of thinking that subtly shape nearly every aspect of our lives, often without our conscious awareness.

Ironically, the ultimate goal of AI development is to mimic this adaptive, abstract, and conceptual thought. Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)—machines capable of reasoning and learning across domains like humans—has lingered as an idea for decades, recently gaining prominence. Yet as AI edges closer to these adaptive capabilities, education seems to be shifting in the opposite direction, increasingly focused on producing compliant task-doers rather than adaptive thinkers.

AI’s impact on filmmaking sheds light on a broader question: as machines become more proficient at creating, how might this change the way we, as humans, learn the art of creation? Filmmaking has traditionally relied on hands-on experience, experimentation, and mentorship. Learning to direct or edit isn’t just a technical exercise; it’s about building creative intuition through trial, error, and a deep understanding of human emotions and storytelling techniques.

The concern is that as AI tools simplify tasks like editing, scriptwriting, and even directing, they may encourage a form of learning that prioritises efficiency over creative exploration. Efficiency has indeed proven useful in my own creative process, especially while making this film. But I’d like to think it hasn’t, and won’t, lead to an outsourcing of intention or ideas.

The risk with overt automation of complex processes is that learning becomes the search for optimisation, for goal achievement—the “AI production of least possible resistance”—eroding the practical and abstract understanding that comes from an intimate engagement with process. In a sense, our algorithmic leaders are steering us toward predetermined styles and audience-tested trends rather than genuine experimentation. Then again, one might argue that humans themselves have created plenty of formulaic content without AI’s guidance.

Reflecting on this, I was reminded of John Dewey’s writings, which affirm that genuine learning is an active process of engaging with uncertainty and discovery—not merely absorbing information or following instructions. If AI begins to influence the learning process itself—determining which shots work best, which genres sell, or which edits create emotional impact—students may lose the opportunity to develop their own vision, instead adopting an AI-mediated understanding of “what works.”Who’s Creative Now?

For the students I spoke with, perhaps the most acute friction in working with AI in creative fields is a fundamental question: is true creativity even possible with AI?

I’m not particularly interested in the hyper-glossy shorts common in brand advertising or music videos—the most prevalent applications of AI filmmaking so far, though limited in scope. While AI has the potential to democratise content creation, allowing anyone to generate art, music, writing, or code, it also blurs the lines of intellectual property, challenging traditional ideas of authorship and potentially undermining the livelihoods of human creators whose work AI often uses for training.

However, the trade-off is a looming concern: the risk that AI could homogenise creativity, generating works that conform to patterns recognised by algorithms rather than unique visions. Trailers, such as those produce by Abandoned Film on YouTube (see the Jurassic Park one here) are undoubtedly impressive. But this work do buttress the argument, that AI causes a flattening of creativity, even though a lot of human labour has gone into the assemblage of this kind of work.

One question I keep returning to is how we define our roles in the creative process. In a sense, identifying oneself as an artist, writer, or filmmaker can be arbitrary, a self-assigned label shaped by cultural expectations. Personally, I feel a certain resistance to calling myself a filmmaker, despite having “created” a film that uses repurposed video footage alongside AI-generated audio-visual elements through programs like Krea, Runway, and Elevenlabs. I credited myself generically as “Created by,” but “Editor” or “Video Essayist” might be more accurate descriptors.

This hesitation stems from a sense that what I’m creating is something distinct—a new form of audio-visual media that doesn’t quite fit traditional definitions of filmmaking. But for student filmmakers, the rapid emergence of AI models like Runway, Krea, and LTX Studios is both exhilarating and unsettling. On one hand, these tools grant access to high-level editing and effects that typically require expensive equipment and years of technical expertise. On the other, they prompt challenging questions about originality and creative ownership. If these models can generate footage, manipulate scenes, and replicate stylistic nuances at the click of a button, where does that leave the student’s own creative input? There’s a legitimate concern that dependence on these tools could erode foundational skills in composition, lighting, and pacing—the techniques that make filmmaking a craft as much as an art.

For students learning traditional filmmaking, the question arises: how, or even if, these tools should fit into the curriculum. There’s a tactile craft in filmmaking—setting up shots, working with light, guiding actors, and manually handling editing software—that feels integral to storytelling. Introducing AI into the learning process might risk sidelining these foundational elements. However, with thoughtful framing, studying these AI models could offer a unique learning opportunity, inviting students to see them as tools rather than replacements. By teaching AI as a supplement to traditional methods, students might explore how these technologies can enhance specific aspects of filmmaking while emphasising that, ultimately, creativity lies in the choices we make and the stories we shape.

Positive or Negative Disruption?

Every significant technological shift brings resistance. But to me, this isn’t simply “Luddite” thinking; the issue isn’t technology itself but rather the lack of thought given to its social and cultural impacts. New technologies often arrive with the allure of innovation, but their broader implications—for job markets, skill sets, and communities—are frequently sidelined in the rush to adopt them.

The real question isn’t just about AI as a technology; it’s about the conversation we’re failing to have around it. Globally, we’re undergoing an economic transformation shaped by an aging population, rapid AI integration, and a shift from globalised economies toward localised manufacturing. Yet our discourse remains shallow, often focusing more on AI’s capabilities than on the restructuring it demands. While AI’s potential is hailed as revolutionary, corporate interests often frame it as a digital panacea, marketed as the solution to everything—frequently without the necessary ethical, social, or economic considerations.

If the benefits of AI remain confined to a technical elite, society risks widening economic divides, potentially eroding the middle class. Companies are racing ahead with new AI capabilities, but public understanding lags dangerously behind, and the window for proactive preparation is closing.

To bridge this gap, we need to ask challenging questions: How can we ensure that AI complements rather than replaces human skills? What training will equip workers to transition into new roles rather than face obsolescence? Without this informed, proactive dialogue, AI’s transformative potential risks becoming mere “background noise” amid constant innovation, and we miss a crucial opportunity to guide this change intentionally.

In the best scenarios, AI can streamline repetitive tasks, boost efficiency, and open up fields for high-skill jobs, liberating human potential for creative and complex work. In filmmaking, this could mean more time for creative experimentation, storytelling, and craftsmanship as machines handle the more tedious aspects of production. However, automation also poses risks to traditional roles, and even in the arts, AI threatens to reshape the landscape, possibly creating a creative field in which originality and unique human expression are overshadowed by AI-driven conformity.

Exploitation and Inevitability?

One student I encountered was firmly opposed to AI, expressing a deep-seated belief in the moral bankruptcy of the technology. Their objections echoed several concerns we’ve explored, touching on exploitation, economic inequality, and the sense that AI fundamentally undermines human creativity and autonomy. This student’s stance had a Kantian inflection, emphasising the intrinsic worth of human beings and warning against treating others—or humanity itself—as mere means to an end.

We undoubtedly have to continually question whether AI development prioritises profit and efficiency over human dignity and the nurturing of human potential. However, I wondered if the student’s rejection of AI was based on a narrow political discourse. I challenged them on other pervasive technologies with harmful impacts? Consider the ubiquity of mobile phones or air travel. Both of these technologies have far-reaching effects, from manufacturing exploitation to environmental consequences, and they, too, are far from neutral.

Perhaps AI represents a continuum, an exacerbation of exploitation that we may no longer afford to ignore. But is technology the problem, or is fundamentally the late-capitalist model we are clinging to, ultimately, what needs reforming?

During the second Q&A session, another student raised the question of environmental impact, highlighting one of AI's often-overlooked issues: its energy consumption. Large-scale AI models require vast computational resources, creating a carbon footprint that complicates, to say the least, AI’s role as an ally in sustainability.

I’m fully in favor of grounding all technological use on a sustainable footing; we can’t ignore that much of modern progress in the global north has historically relied on the exploitation of resources in the global south.

Proponents of AI often highlight its potential to optimise energy use, advance sustainable technologies, and monitor environmental changes—benefits that could significantly aid in the fight against climate change. However, these arguments can sometimes feel like justifications for moving forward without reckoning with the full moral implications. This ethical tension reflects a broader debate within moral philosophy: does the end justify the means?

AI’s trajectory shouldn’t be driven solely by utility but by thoughtful engagement with the ethical stakes involved, especially as it reshapes our ecological and social landscapes. In this sense, the questions students are raising aren’t merely technical concerns but essential moral interrogations that will define how—and why—we integrate AI into our future.

Simulating Human Connection

In the end, perhaps the core concern in Do You Want To Hear It Talk? is the possibility of a more integrated future of human-machine interaction, particularly in terms of the voice and its importance in human connection and expression.

AI is now capable of generating content that can deploy and refine the structures of storytelling developed over thousands of years. It can mimic and hyper-realise the tropes of “humanness” we’ve come to know through cinematic representation over the past 120 years.

At the risk of falling into a rabbit hole of esoteric postmodernism, Jean Baudrillard’s concept of the simulacrum—the notion that representations can become detached from any original reality—resurfaced in my mind. Are we approaching a cinematic future where stars and characters are made immortal by AI software, frozen in their prime, endlessly repeating formulaic stories crafted not for insight or connection, but for passive consumption?

In such a world, films risk becoming mere simulations—empty forms of “connection” that no longer reflect the depth of human experience.

I once wrote a tongue-in-cheek piece about the prospect of Tom Cruise potentially aging in reverse on screen, preserved forever in his prime. Perhaps we’re closer to that reality than I dared to suggest.

The Curious Case of Tom Cruise

It’s Mission Impossible: Dead Reckoning Part 1 opening week in the UK. The latest instalment in what, for my money, is the most consistently entertaining action franchises is, as usual, buttressed by a marking and PR machine with Tom Cruise front and centre. Much of the implicit and explicit media narrative of the press tour expands on the mythos create…

Yet, one could argue that humans have always used technology as a tool for self-expression, continually evolving alongside our creations. AI, seen through this progressive lens, might simply represent another stage in that evolution—an extension of our longstanding fascination with innovation and reinvention.

With thoughtful integration, AI could open doors to previously untold stories, amplifying voices and perspectives that have been overlooked. Rather than replacing human creativity, AI might empower filmmakers to push beyond their limitations, encouraging diverse, imaginative storytelling that reflects the full complexity of human experience. Perhaps AI could even expand our understanding of identity, mortality, and creativity, offering tools that enable artists to explore new dimensions of what it means to be human.

In its own small way, my work aims to interrogate this supposed new era of self-determination and creative freedom, while also reflecting on the questions and fears about what it means to be human in a world increasingly shaped by machines.

This piece has ended up being longer than I anticipated. The complexities of the issues and my struggle to articulate them are by no means fully resolved here. Congratulations if you made it to the end.

Here are the opening few minutes of Do You Want to Hear it Talk? If you work in an educational or industry context and might be interested in screening the film with a lecture or a Q&A, don’t hesitate to get in touch (drdario22@gmail.com).

For paid subscribers, I have included the live audio of the Q&A at Falmouth University and 10 references to further reading/listening which has informed my thinking, and a list of AI filmmakers/thinkers to follow on LinkedIN.

You can access if you join as a paid subscriber for only £3.50 a month

If any readers of this post, whether working in a university or a commercial context, would like to arrange a viewing of the film and a guest lecture/Q&A. Please don’t hesitate to contact me drdario22@gmail.com

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Contrawise to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.