Cinema: Isn't this Nostalgia all a bit sentimental?

Leos Carax Holy Motors (2012) is one of my favourite films of all time. It's a playful meditation on the death of cinema which, ironically reminds us of everything cinema is (and still could be).

Welcome Friends, I appreciate you coming back for more of my musings. There are so many of us musing the crisis, malaise even death of cinema. This ennui is not new. Filmmakers, critics and cineastes of all stripes have been lamenting it, well, more or through through the forms entire existence. For this piece, I want to take you back to 2012, to a filmmaker and film that takes this cliched existentialism, and reforms it through jouissance. A term formed by Jaques Lacan, a deeply unsettling feeling pleasure and pain intertwined.

Before I get into the piece I just wanted to thank for becoming a paid subscriber. It’s so humbling when one bestows this trust and support that a subscription represents.

Also, with the images, this piece is longer than email allows. Better to read it on the Substack app or desktop.

OK, here we go.

What does it mean to live one’s life through cinema?

For some of us, film is not simply a medium among many, not just a form of escape or a diversion from the banalities/relentless/crises of the everyday. It is a condition of being. A prism through which the world is refracted, a grammar of experience, a costume of the subconscious.

Stanley Cavell, in the preface to The World Viewed (1979), articulates this entanglement between cinema, subjectivity and memory with typical elegance:

Memories of movies are strand over strand with memories of my life. During the quarter of a century (roughly from 1935 to 1960) in which going to the movies was a normal part of my week, it would no more have occurred to me to write a study of movies than to write my autobiography.

A World Viewed - Stanley Cavell

This interweaving of film, memory, and self is, I suspect, more common than we tend to acknowledge. It’s not only fully realised cinephiles who carry fragments of films like dreamscapes or diary entries. For me, some of the earliest imprints on my consciousness were cinematic. As a child, the opening credits of Richard Donner’s Superman - those streaking blue titles and that thunderous John Williams score -enveloped me in a sense that something vast, mythic, and far beyond my comprehension was being revealed. It was as if a portal had opened, offering an escape from the narrow limits of my everyday world into a space of spectacular possibility.

I remember being 14, hands trembling with excitement as I slid an illicit VHS copy of The Terminator into the machine. My best friend Robert had procured it from his local video store, whose owner’s questionable morality facilitated what become a clandestine film club of two.

Years later, watching Pierrot le Fou at university, I emerged from the screening and sat, dazed, in the pub. Something fundamental had shifted, about film, about life, about how the two could blur.

Cavell’s wrestling with cinema as metaphysical chaos - where dreams, memories, fantasies and emotions are somehow stabilised by mechanical reproduction - is the ever unfinished idea that we film lovers feel, with an unfathomable intensity. Cinema, he suggests, is less a thing than a paradox. One that resists resolution, yet invites us to return to it, again and again.

To try and unravel this paradox in a few paragraphs is, of course, a Sisyphean task. And yet, isn’t that the joy of cinephilia? To chase that elusive feeling, to hold on to the ghosts that flicker on the screen.

But if cinema is the filter through which subjectivity is formed, what are we left with if, as we are constantly told (and can’t help but think), cinema is dead?

The opening sequence of Leos Carax’s Holy Motors immediately sets the stage for a meditation on cinema and subjectivity. Over the credits, we glimpse flashes of Étienne-Jules Marey’s photographic movement studies - a direct nod to cinema’s primordial origins. It is as if the film is tracing its own DNA, evoking the ghostly mechanics of motion that predate narrative.

Cut to a wide shot: an audience seated in a theatre, still and silent, but with their eyes closed. Are they dreaming? Is this cinema in its purest form - not what is seen, but what is imagined? The screen remains hidden, but the soundtrack plays on. Car horns. Footsteps echoing on hard flooring. A door creaks open. A panicked male voice: “No! No! No!” A gunshot cracks the silence. Then, abruptly: seagulls, the mournful wail of a boat horn, the rhythmic pulse of waves.

Are we being asked to construct the cinematic experience from sound alone? To conjure images through the echos of aural traces? Here, Carax suggests that cinema begins not with the eye, but with the ear, or perhaps even deeper, within the scattered fragments of the unconscious. Cinema is the mind’s instinct for montage: the ability to take shards of sound and flickers of image, to resonate with them, and to reassemble them into something tangible.

If cinema, at its most pure, doesn’t “show to tell”. Rather imprints the possibility of association; this is why a black screen with sound such a potent cinematic expression.

The sequence unfolds in a shadowy, surreal register - the waking dream, or Lynchian fugue perhaps. A sleeping figure stirs and lights a cigarette. It is Carax himself. He paces a dim, ramshackle hotel room that overlooks an airport runway. One wall is covered with a painted forest, thick and impenetrable. Carax raises his hand - his middle finger transformed into a metallic, prosthetic key - and inserts it into the wall. With a turn, a hidden door creaks open. He steps through a narrow corridor and emerges into a cinema auditorium.

We hear again the disembodied soundtrack: footsteps, waves, voices. Carax now stands on the balcony, gazing down at the audience below - still, silent, eyes closed. A small child wanders the aisles. Then a cut to ground level: a huge black dog prowls, unseen, between the rows of passive spectators. Back to Carax, illuminated in profile by the shaft of light from the projector - an image once ubiquitous, now almost mythic.

This opening is saturated with symbolic resonance.

Is this a dreamscape - a projection from the director’s unconscious?

A gesture toward the inseparability of reality and surreality in cinema?

Does the presence of the child signal regression - a return to a primal state of spectatorship?

And what of the dog? A harbinger? A phantom of instinct or dread?

Is Carax suggesting that cinema is less a material form than a conceptual one - an idea we step into, like a corridor behind a wall?

This opening sets the film’s tone. Holy Motors is to be a film about cinema. By a filmmaker contemplating not just the end of an art form, but the dissolution of a self that has been formed by that art. Love, violence, death: these allusions saturate the film’s surreal tableaux. But so too do flamboyance, absurdity, and play. Carax’s tone veers from the melancholic to the carnivalesque, circling a core of dark irony.

A cinematic elegy, yes - but one animated by a kind of ecstatic inquiry. A playful despair. What I’m going to call cinema’s existential jouissance.

This anxiety over cinema’s future hasn’t just haunted industry discourse or audience habit—it has rippled into the texts of films themselves. And perhaps just as significantly, into the methodologies of film studies, which, like the industry it critiques and chronicles, often depends on a relatively stable conception of what “cinema” is.

To be clear, cinema reflecting on itself is nothing new. The medium has always carried a self-referential impulse - through homage, parody, nostalgia, intertextuality, or outright metafiction. One could argue that all films are, in some measure, about cinema. But over the past two decades, there’s been a perceptible shift in tone. What was once a celebration or critique has become a kind of mournful introspection.

There was an especially palpable cycle in the late 2000s and early 2010s - perhaps a transitional moment when social media and streaming were emergent rather than ubiquitous. Still, filmmakers seemed to sense that something was slipping. Something fundamental.

Films from various contexts, and very different aesthetic registers like Martin Scorsese’s Hugo, Tsai Ming-Liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn, Olivier Assayas’ Clouds of Sils Maria, and Pablo Larraín’s Tony Manero each, in their own way, confront the fragility of cinematic memory, the erosion of cinephilic ritual, or the spectral presence of obsolescence.

Holy Motors premiere at Cannes in 2012 coincided with another film that can be positioned in this cycle: David Cronenberg’s Cosmopolis The thematic and symbolic resonances between the two are striking. Both centre on enigmatic protagonists drifting through a city in white stretch limousines - vehicles that function not just as transport, but as liminal zones, sealed off from the world, staging grounds for performance and decay.

Neither film adheres to linear narrative or straightforward exposition. Instead, they unfold in gestures and signifiers, as if deliberately resisting coherence. Their forms enact the very questions they pose: How do we narrate a self when the structures that shaped us - economic, aesthetic, technological - are dissolving? What remains when meaning, as a stable referent, becomes untenable?

These are not just cinematic questions. They are existential ones.

Holy Motors stars Denis Lavant as Monsieur Oscar, a shape-shifting performer whom we follow through a series of cryptic “appointments,” each involving the enactment of a radically different persona. A corrupt banker, an elderly beggar woman, a motion-capture acrobat, a weary father, a dying uncle, a hitman, a lost lover and, of course, the grotesque leprechaun-like figure known only as Merde (French for “shit”), who is a recurring character in several Carax-Levant collaboration.

Who orchestrates these roles? For whom are they performed? And why? These questions remain deliberately suspended. From the opening sequence - and given Carax and Lavant’s long-standing collaboration across five films - it’s hard not to read Oscar as the director’s surrogate, a wandering vessel through which Carax channels his own fragmented subjectivity.

As an aside I saw Denis Lavant in a screening of Carax’ recent C’est Pas Moi (2024) at the Institute of Contemporary arts in London. Lavant was everything I hoped he would be, Carax’s latest continues the inspective reflections of cinema and self-hood, through a kind of cut-up autobiographical experimentalism. I wrote about it here.

Oscar’s fluid transformations challenge the very idea of a coherent or authentic self. Identity here is not something hidden beneath performance; rather, it is performance - assembled, situational, and contingent. The personas he dons are not masks obscuring a “true” self, but tools for navigating a shifting, unknowable world. And notably, these roles do not unfold on recognisable film sets. They emerge within a hybrid space, neither clearly real nor explicitly fictional.

What’s remarkable is how the film’s visual language morphs to match each appointment. As Saige Walton writes:

Holy Motors adjusts its stylistic attitude to meet the demands of each new act. The metamorphoses of Oscar’s body are matched by stylistic metamorphoses on the part of the film. Here, feeling is made manifest in and through movement and the intentional focus of the camera, rhythm, or different uses of film style as much as it is through dialogue or a character/performer’s actions.

The beauty of the act - Figuring film and the delirious baroque in ‘Holy Motors’ by Saige Walton.

Indeed, the film becomes a catalogue of cinema’s own stylistic possibilities. The sweeping camera movements of the musical interlude, the static intimacy of domestic trauma, the uncanny layering of digital and physical space in the motion-capture sequence - each evokes a distinct mode of cinematic aesthetics and “beingness”.

Carax is not just experimenting for its own sake. He’s placing his surrogate - this protean performer - at the centre of a universe where the self, like cinema itself, is in flux. A medium in metamorphosis, navigated by a man made of masks.

Oscar is transported to each appointment by Edith Scob’s Celine, in a white stretch limousine that functions as far more than just a vehicle. It is a mobile metaphor, laden with symbolic potential. On one hand, it evokes spectacle and ostentation - a rolling theatre of transformation. On the other, it offers anonymity, elitism, and isolation: a vessel that glides through the city while remaining entirely sealed off from it.

The interior is cavernous, almost Tardis-like in its defiance of spatial logic. It contains all the tools and prosthetics of Oscar’s metamorphoses, and in this sense, it resembles a behind-the-scenes chamber of cinematic production - a private dressing room masquerading as a machine.

But the limo also takes on a deeper, ontological role. It is Oscar’s liminal life-raft, a space between identities where he momentarily exists outside performance. Here, we might catch glimpses of a “real” self - though that very notion is fraught. Is this a contradiction, or simply another performance, subtler, less codified?

Oscar moves from scene to scene, role to role, adapting to each new context without apparent reason or resolution. He performs because that is what the world requires of him, but the rationale, the destination, remains elusive.

The intertwined play of cinematic language and subjective experience in Holy Motors mirrors the psychic dance between eros and thanatos. Sex and death are, arguably, the twin drives of cinema itself. But Carax doesn't just thematise these forces, he pushes them into a zone of surrealist excess, where desire, violence, and identity become grotesquely estranged from meaning.

Whether it’s the libidinally bizarre encounter between Merde and Eva Mendes’ supermodel, the hyper-eroticised motion-capture sequence, or the cruel dismissal of a daughter by her father - “Your punishment is to be you, to have to live with yourself” - Carax distorts the emotional coordinates of these scenes to induce not catharsis, but disorientation.

This destabilising effect reaches its apex through Carax’s use of death and doubling. In the gangster vignette, Oscar murders a rival and then calmly begins to assume the man’s identity - cutting his hair, changing clothes. But both characters are played by Denis Lavant. As he transforms, the “victim” suddenly stabs Oscar in the neck. They collapse together, side by side. We cut, abruptly, to one of them staggering back to the limo to meet Céline - but which one?

The edit severs any continuity we might cling to. The notion of a “real” Oscar is lost in the cinematic cut. In another scene, Oscar dons a mask and leaps from the limo to assassinate the banker version of himself from a previous appointment - only to be shot down by security. As he lies bleeding, Céline arrives and gently whispers: “Monsieur Oscar, come on, we’ll be late.”

Time, space, even death, are rendered meaningless in this dreamlike cinematic logic. Doubling becomes a central metaphor for psychic rupture - the haunting sense that somewhere, another version of you is living more truthfully. That you are the performance, and elsewhere, the “authentic” self persists.

Carax teases the possibility of an infinite number of Oscars, each inhabiting a different cinematic world, living out parallel roles. The film doesn’t ask what is real? so much as how might one live authentically within illusion? That is its existential quandry. And it is, of course, a profoundly cinematic one.

References to Godard, René Clair, Jean Cocteau, and Georges Franju - as well as echoes of Carax’s earlier work - all attest to Holy Motors’ deep self-reflexivity.

The film doesn’t just reference cinema’s past; it folds it into its very form.

But this is more than homage or citation. The film’s flamboyant, ecstatic, surrealist intensity, is insistent push against the boundaries of cinematic grammar. A interrogation of cinema’s essence. A test of its limits. Perhaps even a rupture.

This is where the concept of existential jouissance becomes useful.

Drawing from Lacan, jouissance is distinct from plaisir. While plaisir is pleasure contained by the pleasure principle - bound by rules, social acceptability, and the avoidance of pain - jouissance is the point at which pleasure tips into excess. It is transgressive and marks a psychological breach where enjoyment becomes unbearable, ecstatic, or even destructive.

Jouissance is the drive beyond the boundary, the compulsion to confront the void where identity, coherence, and even pleasure itself begin to unravel.

In this light, Oscar’s episodic performances - each saturated with eros and thanatos - can be read as acts of jouissance. They are not simply performances within performances, but confrontations with excess: of form, of feeling, of meaning. The repetition of death, the constant slippage of identity, the film’s refusal to resolve into narrative closure, all become symptoms, expression or evocations of this jouissance.

And on a meta-level, Holy Motors can be read as reveling in the jouissance of cinema itself - its dissolution, its transformation, its potential death. Carax doesn’t mourn this loss; he stages it. And in doing so, he locates a strange ecstasy not in the survival of cinema, but in its breakdown. Its transfiguration.

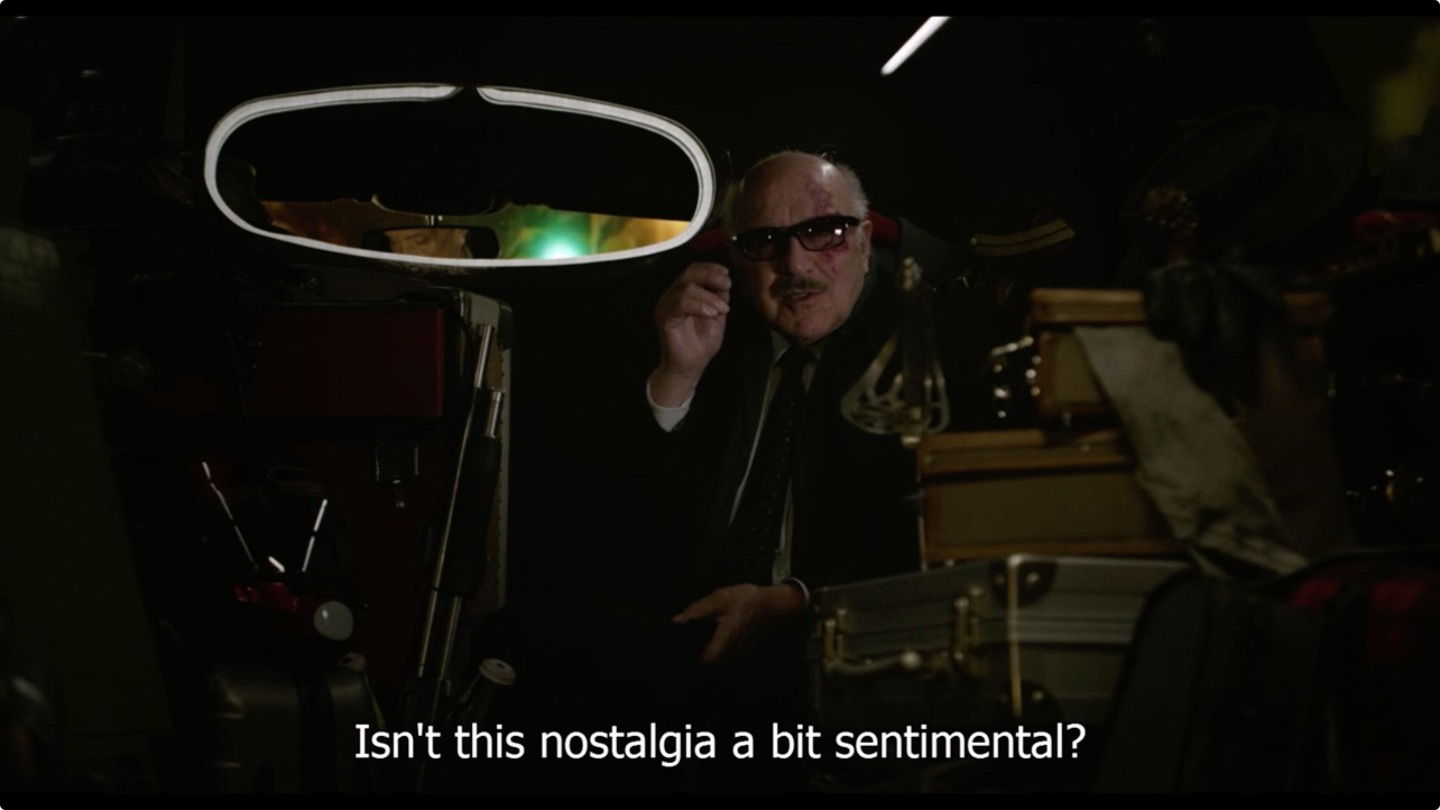

A key moment in which some semblance of narrative and thematic context emerges occurs when Oscar returns to the limousine following the gangster sequence. Waiting for him in the shadows is a figure who seems to occupy a position of authority—perhaps even authorship. This scene offers a rare instance of direct dialogue that gestures toward the purpose - or futility - of Oscar’s performative journey. I’ll play this clip now, and then offer some commentary on how it crystallises the film’s existential concerns.

In one of the film’s few scenes that offers something resembling narrative exposition, we glimpse a shadow of context - an implication that Oscar’s performances take place within a futuristic, post-cinematic world.

A space where construction and reality have collapsed into one another, forming a simulacrum so total that its artificiality becomes indistinguishable from authenticity.

Oscar’s lament - “I miss the cameras... It’s harder to believe in it all now” - is especially revealing. It suggests a paradox: that the presence of visible cinematic apparatus once enabled a sense of purpose, of belief. In their absence, meaning disperses.

Here the concept of the dispositif becomes instructive. Used by theorists such as Baudry, Bellour, and Deleuze, the dispositif articulates the unique perceptual configuration that cinema offers: the alignment of spectator, screen, and space to produce a particular kind of embodied immersion. The darkness of the auditorium, the fixity of the gaze, the collective stillness - these elements create a phenomenological condition through which the film can unfold as more than image: as presence, as memory, as dream.

Where, then, is the audience? Oscar knows he is being watched, but by whom? And through what means? The suggestion of a surveillance mechanism evokes the Foucauldian panopticon - an omnipresent, anonymous gaze that disciplines through visibility. Or perhaps more aptly, we are in a Truman Show-like universe, where the architecture of reality is constructed entirely for performance, overseen by an invisible, possibly indifferent, viewer.

Could this anonymous gaze reflect the digital spectator - decentralised, fragmented, everywhere and nowhere? In the streaming age, viewership becomes disembodied: the audience is diffuse, metrics-based, abstract.

We consume, but are rarely present.

This raises a final, poignant contradiction. Cinema has historically aspired to ever greater realism - from painted backdrops to virtual environments. But if cinema were to achieve a “perfect” simulacrum - an unbroken illusion - perhaps when AI’s fakery becomes the default verissimilitude - would it still be cinema? Or would its very essence, its poetic gap between reality and representation, be obliterated?

The title Holy Motors may itself be a metaphor for cinema: a mechanised medium imbued with something sacred. Something luminous.

What the film offers is a kaleidoscopic tour through cinema’s many dimensions—past, present, and speculative; real and surreal; subjective and objective; material and cognitive. But more than that, Holy Motors engages, at a deep and visceral level, with the existential anxieties of the cineaste—those of us who have lived not just with cinema, but through it.

In this moment, perhaps more than ever, we are being forced to confront the ontological dimensions of the cinematic. What is it, really? What has it become? What might it still be?

If, as Sartre suggests, existence precedes essence, then perhaps Holy Motors intimates that a complete, authentic, essential cinema never existed in the first place. Or if it did, it was a mirage - an assemblage born of contingent artistic, technological, social, and economic forces. A beautiful accident.

Take the coming of sound. One could argue that silent cinema always already contained the latent potential for synchronised sound that it was merely waiting for technology to catch up. When sound arrived, did cinema become what it was “meant” to be? Perhaps. But that line of reasoning presumes a fixed endpoint, a cinematic telos.

And if we grant that to sound, must we not extend the same logic to every subsequent transformation? Colour, widescreen, video, digital, streaming, AI? Each new form might be seen not as a break, but as part of the becoming of cinema.

Still, for those of us whose sense of self has been shaped by the classical notion of cinema - as ritual, as artform, as cultural anchor - the dissolution of that model under digital pressures can feel like loss. It can feel like death.

And yet Holy Motors resists this despair. It confronts these existential questions head-on, but does so through excess, exuberance, and play. It stages the crisis not as a collapse, but as a metamorphosis. Through its delirious movement across genres, styles, identities, and moods, the film dares to suggest that cinema’s death may, in fact, be its transformation.

And perhaps, its rebirth.

Thanks for reading this latest piece in Cinema Body/Cinema Mind. If you liked what you have read I’d really appreciate if you can restack/share to your networks. This is a gesture of human curatorial practice which works better than any algorithm recommendation.

If you’re not already a subscriber, please consider doing so by hitting the button below. Become part of the network of curious, fascinating people!!

A paid subscription is £3.50 per month and you will get access to the full articles and podcasts I produce. There is a lot of work that goes into the writing and podcasting, so becoming a paying subscriber really help support the continuation of the work.

I’ll also send you and physical postcard, wherever you may reside, how can one resist:

If you don’t want to subscribe but could see your way offering a small tip the labour of producing the work, hit the button below.

For paid subscribers below is a list of resources and recommendations of reads from FilmStackers who continue to inspire and influence me.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Contrawise to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.