London Film Festival - round up

Of the small selection of films I caught from a stacked LFF this year, there were no read duds, a few puzzlers, some connecting themes, and a potential classic.

I was in and out of the London Film Festival this year. But our coverage for The Cinematologists Podcast was the most extensive we’d ever undertaken. Two main episodes and Four bonus episodes were made possible by two new contributors Ben Goff and Hailey Passmore who have us fresh and astute insights.

Access to our the best indie film coverage and a growing cinephile community is available on our Patreon site. www.patreon.com/cinematologists.

The main show is also available wherever you listen to podcasts:

Podfollow, Spotify, Apple Podcasts

<iframe title="The Cinematologists Podcast" allowtransparency="true" height="315" width="100%" style="border: none; min-width: min(100%, 430px);height:315px;" scrolling="no" data-name="pb-iframe-player" src="https://www.podbean.com/player-v2/?i=hs4zw-31afdf-pbblog-playlist&share=1&download=0&fonts=Georgia&skin=3267a3&font-color=&rtl=0&logo_link=&btn-skin=60a0c8&size=315" loading="lazy" allowfullscreen=""></iframe>Alongside that here are a few thoughts on the films I saw:

The Nickel Boys (★★★★★) RaMell Ross

Emerging from the press pre-screening (some ten days before the LFF proper began), I ran into my fellow critic from The Cinematologists Ben Goff. We exchanged inquisitive eyebrow arches. I asked, “Was it just me, or did we just witness some verging on brilliant?” He nodded a kind of conspiratorial agreement. The tale of a sliding doors moment derailing the life of a promising, sensitive, and talented Black kid in the Jim Crow South, is told softly, yet with an undercurrent of furious injustice. Ross deftly wields with a delicate authority, making it not just a camera angle but literal, literary, and figurative prism for the shaping of an empathetic gaze. Faithful to Whitehead’s narrative, particularly the dexterous time-shifting, Ross invokes a symbiotic psychology of resistance/resilience.

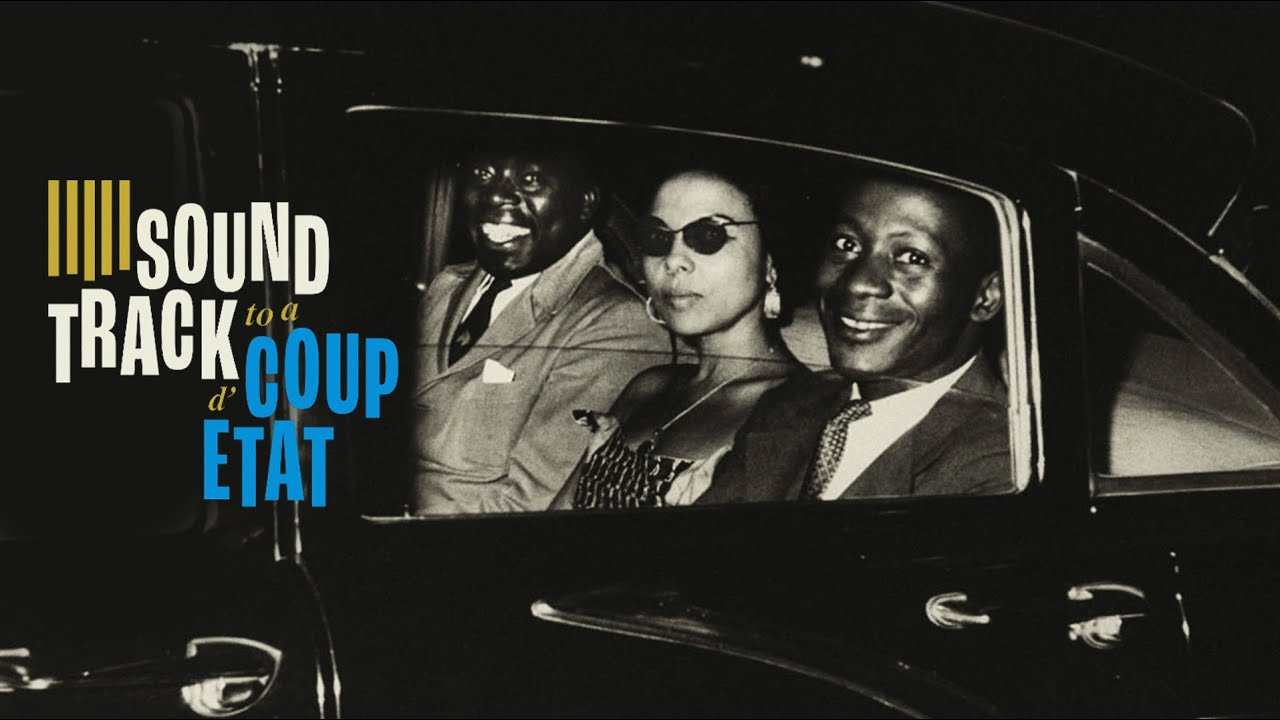

Soundtrack to a Coup D’etat (★★★★½) - Johan Grimonprez

A riveting, sprawling essayistic documentary that asserts the essential rhythmic symbiosis between cinema and music. The incredible, almost surreal, tale of America’s jazz legends—Louis Armstrong, Nina Simone, Duke Ellington, and Dizzy Gillespie—unwittingly co-opted as ambassadors for America in a chess match of colonial geopolitics with Russian Premier Khrushchev. The overthrow of Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, who wrestled his country’s independence away from Belgium while advancing a pan-Africanism, put him at odds with both Cold War powers. Eschewing the potential stiltedness of talking heads, the sonic texture pulses with a feverish urgency, images crash against each other, quotation have to be imbibed like shots of indignation.

Maria (★★★★ ½) Pablo Larraín

Angelina Jolie’s performance dominates a film that is less a biopic and more a meditation on the performance and construction of iconicity. Fascinatingly, you never forget it’s Jolie, no matter that it’s Maria Callas’ life mythology. Through the extreme close-ups, the lip-synching, and indeed the entire production design, Jolie never “disappears” (in the way Bradley Cooper attempts with his prosthetically assisted Leonard Bernstein impression). Larraín, through the Jolie/Callas hybrid, teases out the performance through layers of interplay between the symbolic and the tangible, the glorious and the tragic. More of a companion piece to Jackie in tone and style, Diana feels like an odd diversion. The visual texture—from gauzy sepia 1970s film stock to theatrical black and white to faux 8mm home movie—invites a luxuriously nostalgic eye. In one of many wonderful diva-ish exultations, Jolie/Callas states: “I don’t go to restaurants to eat; I go to restaurants to be adored.” A defiant encapsulation of a life both created and destroyed by the public gaze.

Dahomey (★★★★) Mati Diop

Blending documentary with poetic, imagined elements, Diop explores the repatriation of 26 artefacts from France to Benin, formerly the Kingdom of Dahomey. Central to the film is the statue of King Ghézo, who ruled from 1818 to 1859. Its journey back to Benin is narrated from the statue’s perspective, voiced by Haitian writer Makenzy Orcel. The voice-over reflects a historical disorientation, as the colonial trauma endured during decades of “imprisonment” is finally given a chance to articulate itself. Diop juxtaposes the logistical process of transporting the statues with the symbolic weight of their return, as experts and onlookers receive them with reverence and exuberance. While only 26 of the 7,000 looted objects were repatriated, the film offers a fascinating meditation on the legacy of colonial exploitation, anti-colonial reclamation, and the use of cultural restitution as political capital. Slow, trance-like shots—particularly of archaeologists gazing in awe—highlight the statues’ power, not just as objects of beauty, but as witnesses to a reclaiming of identity. The second half of the film shifts focus to a group of students debating, remembering, and asserting. Their voices express the struggles of youth as they seek to ascertain and reclaim a sense of "self" in the context of a fragmented national identity.

Harvest (★★★½) Athina Rachel Tsangari

There is a tactile strangeness to Harvest, a film that begins as a study of medieval Scottish life, only to slowly reveal its larger preoccupations—fear, conquest, and the inexorable march of capital. Caleb Landry Jones plays Thirsk with a restrained (for him), yet visceral kind of intensity, all grit and lust, his world on the brink of collapse not just from external threats but from the very logic of expansion creeping in from outside. Enter Quill, a mapmaker of quiet charisma (played by Arinzé Kene), who charts the landscape with both beauty and betrayal. His complicity with the English landowner signals not only a shift in ownership but in the very concept of space, and with it, the expendability of those who inhabit it. Tsangari crafts an anthropological puzzle, unsettling but engrossing. An quintessential festival film, it’s difficult to see how it will be placed for a wider audience?

Under the Volcano (★★★½) Damien Kocur

A middle-class Ukrainian family prepares to return home from a holiday in Tenerife. When the war erupts just as they are about to depart, they find themselves stuck in limbo. Returning to the hotel, the simple banalities of a packaged vacation become a dark, almost surreal backdrop to the increasingly strained dynamics between the parents. Kocur smartly keeps the war itself off-screen, allowing its presence to haunt the family’s every conversation, every gesture. Shame and embarrassment are as palpable as fear. The personal and political intertwine through social interactions and psychological reactions, as inescapable dilemmas loom larger, tightening the spiral of trauma.

Anora (★★★) Sean Baker

Baker’s preoccupation with sex work and situationalism is given something of a mainstream gloss here. The Pretty Woman-esque conceit shifts into caper-slapstick, with the eponymous lead landing a lottery ticket in the form of a wayward Russian billionaire’s son—until his parents' hapless minders catch wind, and reality bites. My expectations were high going in, thanks to the critical praise and post-Cannes buzz. But I see or feel the depth that others clearly have. Films that focus on dislikable, even despicable, characters are fine with me, but there needs to be something compelling about them. And the ending—aiming for an almost epiphanic moment—reaches for profundity without quite grasping it, leaving us in search of something it never quite delivers.

To a Land Unknown (★★★) Mahdi Fleifel

The contradictory feelings of refugees are stirred up in this Athens-set drama, as two Palestinians engage in petty—and not so petty—crime in an attempt to forge a path to Germany. While the script aims to explore how desperation shapes identity, it feels somewhat underdeveloped. Mahmood Bakri is excellent in embodying the ethical compromises of a displaced existence.

We Live In Time (★★½) John Crowley

Effectively directed, but decidedly middlebrow, this tragedy lives and dies—literally and figuratively—on the charisma of its two leads. This is a film that might once have been critiqued from an ideological feminist standpoint: just another film punishes its autonomous, successful and competitive female protagonist, for whom motherhood and wifedom are clearly not enough? Garfield is perfectly cast as the harmless, mediocre white male. The beats leading up to the culinary competition denouement are whole formulaic. It will likely perform well.

The End (★★½) - Joshua Oppenheimer

Musical meets apocalyptic dystopia, yes indeed. The problem, though, is an obvious one: Oppenheimer’s decision to merge these genres feels more like a stylistic gambit than a narrative necessity, and the disconnect is never fully resolved. Michael Shannon’s oil billionaire is still in denial about his role in the apocalype. His wife, Tilda Swinton, will do anything to avoid conversation of those left behind. George MacKay is perfect as the naive man-boy slowly awakening the fictions underpinning his reality, which is accelerated after the arrival of disruptor Moses Ingram. A oddly sentimental and conservative ending was, it seems, in keeping with the incongruity of it all.