Should cinemas embrace the responsibility of film education?

Could cinemas fill a gap in film education left by the universities? Making a long term commitment to a future film-going audience could sustain cinema's own viability.

Welcome, friends. Thanks as always for dropping by.

It’s great to have so many new subscribers reading the work. I've been genuinely humbled by the growth in interest over the past couple of weeks, particularly as much of it has come through engagement with my post on film studies.

It’s actually made me think that there is a desire for this kind of in-depth conceptual work on cinema. The post below leans into that, albeit in a wider social framework sense.

It’s very hot in London right now, just one of many excuses for the procrastination I’ve been wallowing in, especially with this particular article.

This kind of piece is always harder for someone from an academic background. It’s something of a think piece, grounded mostly in personal experience. The final section tries to draw out some reflections on the changing landscape of cinematic education. But while writing it, I kept feeling it was too general, too subjective. I default to the worry that data and citations are a prerequisite for imbuing claims with more weight.

I’ve added a bit of that in, but I promised to myself to keep this platform as more of an experimental practice in shaping, playing with ideas. Maybe I’m just overthinking it. I realise opening a post by apologising for it isn’t the most compelling advertisement for reading on.

Still, I needed to get this out there, rather than continue tying myself in knots trying to caveat every sentence.

Thanks for bearing with me.

The Light Changed

When I was studying film at Sheffield Hallam University, one of the most memorable aspects of the course was heading into town once a week for lectures and screenings at the Showroom Cinema. I lived near the old Psalter Lane campus (closed in 2008), so it was a 15–20 minute bus ride down Ecclesall Road.

I remember the first week of term. Me and a bunch of self-conscious wannabe cinephiles, all performing that carefully calibrated aloofness that masks fresher anxiety. As a 25 year-old “mature” student, and didn’t feel the same “new day of school” jitters. If anything, I affected a kind of stridency about my reasons for being there.

I didn’t live in halls. I stayed with my aunt and uncle in Sheffield from Monday to Thursday, then commuted back to Leeds to work weekends as a manager in an Italian restaurant. I made a few friends on the course but, as is my personality, maintained an independence that took precedence over falling in the undergrad cliques.

Anyway, I digress.

The names of the first-year modules are a little hazy, probably something as straightforward as Introduction to Film History or Understanding Film Language. If I remember right, the rhythm of the course alternated: one week, a double lecture from 9am; the next, a double screening.

The first screenings set the tone. A seminal pairing: Man with a Movie Camera and Battleship Potemkin. These lecturers weren’t fucking around. Two Soviet silent montage epics, back to back. No orientation-week soft landing. No easing in with Chaplin, a breezy noir, let alone something blockbustery.

I’d estimate half the cohort left after the first film. Another chunk slipped out during the second. But I wasn’t going anywhere. This felt like an initiation, a test. And I intended to pass.

Across the next three years, some of my most vivid cinematic experiences happened in that auditorium. I saw Pierrot le Fou there for the first time and walked out feeling like the world looked different, like Godard had rewired my visual cortex. In the genre module, I was introduced to Douglas Sirk’s melodramas, the final scene of Imitation of Life somehow breaching the apathy forcefield of even my most cynical classmates. I remember watching L’Avventura and Zabriskie Point back to back, and then booking out every Antonioni film on VHS to complete his ouvre by the end of the week. I found an article where Antonioni had described himself a “communicator of mis-communication”, a thoroughly impressive concept. I used this to underpin an essay on modernist aesthetics of the pleasures of ennui.

I wasn’t the perfect student. I once fell asleep ten minutes into Diary of a Country Priest, waking with a jolt as the credits rolled and the house lights came up. A late night at the Leadmill nightclub and a 9am screening with Bresson was always going to be a bad pairing.

The Showroom ran student nights on Mondays and Tuesdays—£2 tickets and cheap beer. I saw Fight Club and The Insider there. In seminar the following day, I argued - probably with too much certainty - that both were far superior to American Beauty, which had just won the Best Picture Oscar. It’s an opinion I still stand by. That was also the year of Star Wars: The Phantom Menace, which triggered the fan-versus-cineaste tensions that have since metastasised into the bloated tribalism of online film discourse. A tiresome and damaging turn, especially when serious conversation is what cinema most needs to renew itself.

The key point is this: there was a commitment to genuine integration between cinematic experience and education.

We also watched a lot of films in the university’s auditorium. The place was a converted lecture hall and was definitely in need of a refurb. But despite squashing in together on uncomfortable benches, astonishingly the place still had a functioning 35mm projector. The university had its own collection of prints and hired others in.

Of course, there was plenty of home viewing too. It seems almost archaic to say it now, but in 1999, VHS, dominant for two decades, had only just been overtaken by DVD. The streaming landscape we now take for granted would’ve sounded like science fiction if you’d described it to me back then. Cinematic life (and every other kind of life) existed without mobile phones.

The auditorium, however, remained the physical and conceptual centre of both educational and social life. Our course leader even advocated a specific philosophy of viewing in the cinema, declaring: “Watching films on the small screen is like reading a book with the pages missing.”

This advocacy of collective spectatorship gave the experience a kind of cultural gravity. Around that centre, our engagement with realism, formalism, auteur theory, genre, semiotics, psychoanalysis - all the theoretical frameworks we were absorbing - felt anchored.

And it wasn’t just academic. Those screenings, and the time spent around them, became a crucible for everything intangible: subjectivity, taste, memory, friendship, confrontation, identity, even flirtation. A matrix of connection made possible by the shared knowledge that we’d all been in the same dark room, watching the same moving images, breathing the same cinematic air.

I imbued in me the sense that watching films in cinema are the unique, ideal conditions for spectatorial immersion but also for me the key material space for cinematic, social and cultural education.

2. Cinema Decoupled from Film Education

Cut to 2022. I’d been a film academic for two decades and had just stepped into a new course leadership role. I still believed - naively? stubbornly? - in the anchoring importance of the theatrical experience. But the cultural terrain around cinema had shifted. Even among film students, what once felt like an intuitive, almost sacred assumption—that the auditorium screening was the default mode of film-watching—had eroded.

Over the years, I’ve had hundreds of conversations with students about this. What emerges is not apathy, but a complex matrix of structural barriers, logistical headaches, and subtle cultural shifts that have not only undermined regular cinema-going (even for those inclined), but altered the attitude toward the idea of a unique, specific experience.

The default to streaming has, of course, fundamentally shifted the sensibility of film consumption. The collapse of release windows, the bundling of titles into scrollable thumbnails, and the algorithmic tailoring of recommendations make the physical effort of a cinema visit feel increasingly onerous. As I, and many others, have argued, the reduction of films to mere units of "content" has diminished their cultural and aesthetic specificity.

Film students are as embedded in this shift like everyone else. Film-watching has collapsed into the same screen-space stream of spatial and sensory reception (distraction). The cinema has therefore ceased to be the primary site of encounter, instead perhaps becoming something of a nostalgic abstraction - or at best still lauded as the ideal framework for film viewing, but only of certain kinds of films, often the CGI-driven blockbusters.

Faced with limited disposable income, most students choose the path of least resistance: free or cheap home viewing. Then there’s time. The rhythms of student life - essays, group projects, part-time (sometimes full-time) jobs - are not conducive to having fixed-scheduled screenings. Many course structures have adapted to this reality by no longer scheduling screenings as part of the curriculum. It’s easy to see why in an era of budget cuts. Post-lecture screenings have been replaced by home-access platforms, digital libraries, or resources like Kanopy or Box of Broadcasts. This absence of a collective screening implicitly suggests that communal auditorium viewing is no longer essential to studying cinema.

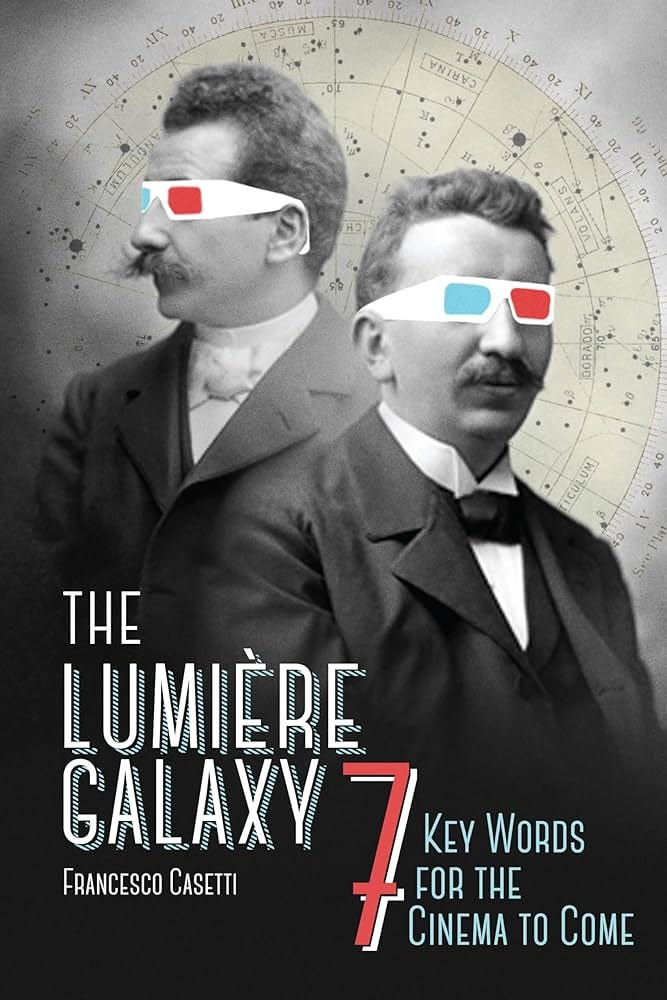

I don’t want to suggest that home viewing, through all the possible avenues now available, is not advantageous to film scholarship. First of all, being able to pause, rewind, analyse frame-by-frame, and take notes aids the kind of discursive “close reading” that is the core methodological approach in film studies. I’ve also heard many stories about how film students essentially recreate a collective viewing experience at home. A big TV or projector, an appointed time, and even guidelines create what film studies scholar Francesco Casetti calls the modern “assemblage” of spectatorship conditions. (His excellent book The Lumiere Galaxy, I highly recommend).

Obviously the social terrain has changed. The digital, rather than the physical, space now offers the potential for an expansion of what Girish Shambu has called the Cinematic Elsewhere: the peripheral or supplementary zones of reflection, discussion, criticism, and theorisation that shape our understanding of the “there” of watching (see The New Cinephilia). Social media, Letterboxd, and the countless forums that have allowed fan cultures to flourish are overwhelmingly digital-first and rarely structured around the physical encounter.

And then there’s the emotional hangover of the COVID years - a lingering inertia, a hesitancy to return to shared public spaces, and its entanglement with a broader malaise around mental health. But that’s a rabbit hole I won’t drag you into right now.

Despite all of this (and to be honest, other factors but I’m trying to get to the point), I was determined to try to reintroduce something like the Showroom-Hallam model as part of my new role.

In the institution where I had started, there wasn’t an auditorium or lecture space that was in any way conducive for 100+ film students to watch a screening (or listen to a lecture, for that matter) and have a sense of being within a cinematic cultural space.

So I reached out to local cinemas, both multiplexes and independents. The criteria was that I needed 150 seats, and the caveat was that I had a paltry budget. I contacted the cinemas through their commercial/hiring emails and was generally met with rather perfunctory responses that simply listed the commercial hiring costs. These ranged anywhere from £1,000 to £6,000 for a single three-hour block, not including staff or film licensing.

If you know anything about university budgets right now, you’ll know that’s not gonna fly.

I spoke to a couple of duty managers at different cinemas, but in reality, their concern was the day-to-day running of the venue. They had no power over the decision-making processes when it came to programming.

Instead, I managed to get hold of the central cinema hiring manager for one of the local multiplexes. I tried to explain what I was offering: a regular 12-week, guaranteed audience at a time that wouldn’t interfere with regular programming. Minimal staff would be required - I’d be there - and there was a possibility of making extra on early morning coffee and food.

The guy just proceeded to quote the commercial hiring price. He seemed completely locked into a kind of narrow, spreadsheet thinking, without the ability to see the advantages of the proposal. Maybe I just hadn’t reached the right person. But when I gave my pitch about filling the auditorium during hours it would otherwise sit empty, suggested possibilities for concession revenue, the chance to sell student memberships, or even collaborate on an end-of-year film festival, it was all met with a list of hourly rates.

While the failure to realise my teaching plan was dispiriting, it spoke to a wider malaise. Perhaps I was naive to expect a knockdown price? Maybe students are more trouble than they’re worth? Perhaps the infrastructure for such collaboration just isn’t there. But beyond all that, what struck me was the lack of urgency - and lack of advocacy - for cinemas and the cinema-going experience.

If you are enjoying read my work please consider the small gesture of dropping me a tip using the button below.

Should Embrace the Responsibility of Film Education?

I’ve long wondered why cinemas don’t more actively seek out formal, fundamental forms of collaboration regarding film education. The anecdotes detailed above certainly crystallised in my mind the potential benefits, but also the attitudinal barriers, that might have impeded more holistic, innovative thinking. Just from a plainly commercial perspective, why cinemas don’t look to utilise their “dead time” more effectively - those empty hours between 9am and noon when most auditoriums sit unused - is a mystery to me.

Surely this gap could be repurposed for education? Maybe there are logistical or cost-based reasons why this doesn’t happen. Yet with a guaranteed audience and lecturers onsite - plus the added economic boost of 100 students likely in desperate need of a caffeine infusion before two-plus hours of Italian Neorealism - I always thought the barrier was more one of mindset.

This becomes more nonsensical when one considers the shifting tectonic plates of both cinema exhibition and film education, each deeply impacted by the techno-social-cultural transformation of spectatorship.

In the current climate of higher education, the arts and humanities are bearing the brunt of austerity. Film studies - especially theory-based programmes without strong vocational elements - are particularly vulnerable. As with media studies, cultural studies, and even traditional subjects like English and History, enrolment numbers have been falling for years. Courses centred around theory, traditionally a space for critical reflection on culture, aesthetics, and ideology, are now low-hanging fruit for those pushing economically driven reforms of learning.

The situation isn’t helped by public perception, fermented largely by the right, that such courses are “soft” or “non-essential.” So-called “Mickey Mouse” degrees continue to be political punching bags, despite their long-standing contributions to critical thinking and cultural literacy. Could it be a class-based agenda that sees universities as institutions for training compliant workers?

Students themselves have clearly imbibed this, both in their rational decision-making and in a more psychological reaction to conceptual approaches to knowledge (this is an idea I want to follow up on in another post).

Specialist film studies degrees have slowly been folded into broader programmes like English, Media Studies and Sociology, Visual Culture, if not axed altogether. In the UK, there are hubs where film studies seems to be retaining healthy interest, such as Warwick, KCL, and St Andrews. I can’t speculate on admissions numbers, but in this climate, fee-paying studies outweigh historical legacy and research reputation.

Within what you might call combination courses, split between practice and theory, the theoretical component is often in conflict with filmmaking. From my own experience - primarily teaching on such courses - students have increasingly gravitated towards hands-on modules they believe are more likely to lead directly to employment.

The tension between “theory” and “practice” has long underpinned film and broader arts education. Mutual suspicion - and occasionally outright hostility - between practitioners and theorists goes back to the ancient Greeks. The distinction between episteme (what we might now call theoretical knowledge) and techne (practical knowledge related to material skills or craft) continues to shadow how these areas are taught.

This dichotomy has been exacerbated by the agenda of the neoliberal university which, in its increasingly transactional approach to learning, has to be seen to guarantee the applied economic value of what it teaches. The arts and humanities have attempted to adapt by emphasising practice as the foundation for a trajectory into work.

This is where I return to my central thesis: cinemas are missing out on an opportunity to become active partners in the cultural education ecosystem. At a time when the rationale for going to the cinema is no longer self-evident to younger generations, cinemas should be looking for ways to cultivate their future audience.

We need new models of collaboration that bridge exhibition and education. This could certainly take the form of formal partnerships, such as the one I benefited from during my undergraduate degree. But it can could also be organised independently by cinemas themselves. Scholars such as myself would certainly me interested in work with cinema in this way, developing a programme of lectures and screening and offering a positive pricing policy doesn’t seem that much of a stretch.

Cinemas should take the lead in creating a new generation of viewers who don’t just treat films as passive “content,” but who understand the historical, aesthetic, and political dimensions of cinema. This isn’t a nostalgic plea - it’s a pragmatic vision.

There’s already a strong foundation to build on. Initiatives like Into Film have demonstrated the educational potential of cinema spaces, particularly in work with schools. Their guidelines for cinemas wanting to collaborate with schools offers a succinct pitch:

Bringing young people into your cinema provides an opportunity for you to begin building an audience for the future. It can help start a vital relationship with them, allows you to promote your upcoming programme and, ultimately, help you sell more tickets - Cinema advisory pack.

This profanatory statement should hit hard with cinemas continually struggling to attract audiences. It doesn’t lean into any flower talk about the ideal cinematic experience.

Reports from cultural organisations, including the BFI and Film Literacy Advisory Group, emphasise that film education increases cultural engagement and media literacy across all age groups. Academic studies in adult education also underscore how participatory learning environments - especially those rooted in shared cultural experiences - can have long-term benefits for mental health, social cohesion, and civic participation.

As it wasn’t already completely obvious, Research from the Creative Industries Policy & Evidence Centre (PEC)uggests that local cinemas contribute to placemaking and social infrastructure, boosting foot traffic for surrounding businesses and helping to define the cultural identity of communities. Embedding education into this model only strengthens that role.

And from a practical standpoint, cinemas already have the space. Most venues sit empty from 9am to noon—it seems obvious that this time could be repurposed for film clubs, community courses, school partnerships, and adult education workshops.

Collaboration between universities and commercial companies is much more normalised in STEM subjects than in the arts and humanities (and more so in the United States than in the UK, to be honest). But frankly, I’m amazed that no major cinema chain has seriously looked into the option of creating and running its own film degree. It could be based around programming, archival work, film criticism, or even practice, and potentially underwritten by a university with degree-awarding powers.

Obviously, I’ve painted this in broad brushstrokes. There are clearly many complexities I’ve either deferred or ignored altogether. I don’t want to suggest here that cinemas, particularly independents are not looking for innovative ways to attract audiences. In London I’m spoilt for choice when it comes to cinema events that have a pedagogic aspect to them.

And this isn’t just about saving film studies in a formal sense, but just from my small ecosystem on substack and the broader conversations I have that are inflected with theoretical/philosophical approaches to the understanding of film, along with a vibrant digital world that still engage with cinema as a specific form, I believe there is an audience/market for that.

Cinemas can reimagine themselves in the post-streaming world.

If you’re a cinema programmer, a venue manager, or someone working in arts education who wants to discuss the potential of this idea, get in touch. I’d be very interested in creating a course as a proof of concept for a cinema, or working with a university and venue to think through the logistics of such an initiative.

This is very much a subject I want to return to. For the FilmStack brethren, the question of cinemas and the film-going experience sits at the forefront of debate - just as much as questions of financing and filmmaking infrastructure.

Very happy to hear your thoughts.

This is a free post available to all.

A subscription is £3.50 per month and you will get access to the full articles and podcasts I produce. There is a lot of work that goes into the writing and podcasting, so becoming a paying subscriber really help support the continuation of the work.

I’ll also send you and physical postcard, wherever you may reside. How can one resist:

I have enabled the free trial function for my Substack so if you want the PDF but don’t want to subscribe just yet, you can do that.

For paid members below I have attached once my PDF entitled 500 Films That Define Cinema 1898-1985) the genesis of which write about specifically here.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Contrawise to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.