Still Not There

Rewatching American Psycho as a 50-year-old and the shifting illusions of masculinity, identity, and cinematic self-projection.

I rewatched American Psycho the other day. One of those out-of-nowhere, algorithmic-surfing moments, when it popped up on Netflix. It’s a film I’ve seen countless times; it was one of the case studies in my MA dissertation on the late-20th-century crisis of masculinity alongside Fight Club and American Beauty (2000 really was a landmark year for men on the edge). I didn’t even clock that it was the film’s 25th UK anniversary until I’d nearly finished writing this piece.

It’s a film that still asserts itself: visually arresting, sharply edited, and self-conscious, with that immersive, intuitive energy that one instinctive knows, this is cinema. At times, it’s overtly funny, but that humour is always undercut, forcing a reckoning with one’s own complicity. Am I supposed to enjoy this the way that I am?

Much of the discomfort lies in the violence, which oscillates between the kinetic verve of slasher schlock and the stylised senselessness reminiscent of A Clockwork Orange. It provokes a kind of existential recoil. And yet, what struck me most on this rewatch was how much of the violence is actually implied. Harron leaves ample space for us to imagine the worst.

As a social satire, the film remains ceaselessly compelling and unnerving. I’ve long considered it a rare case where a film adaptation not only honours the novel but deepens and sharpens its critique. Take Bret Easton Ellis’s fixation on material culture: page after page chronicling what Bateman listens to wears, eats. It’s rhetorically effective, revealing psychopathy through obsessive consumption, but on the page it can feel turgid, numbing. On screen, that excess is translated visually through Bateman's designer-saturated world, while Christian Bale’s coldly arch voice-over layers in his symbolic obsessions, restaurant hierarchies, and brand worship.

Obviously, I’m alluding to one of cinema’s fundamental advantages over literature: its ability to manifest mood through audiovisual dynamics. But what Mary Harron achieves with her adaptation is more than just tonal fidelity—it's a masterclass in deepening a novel’s thematic core through cinematic language.

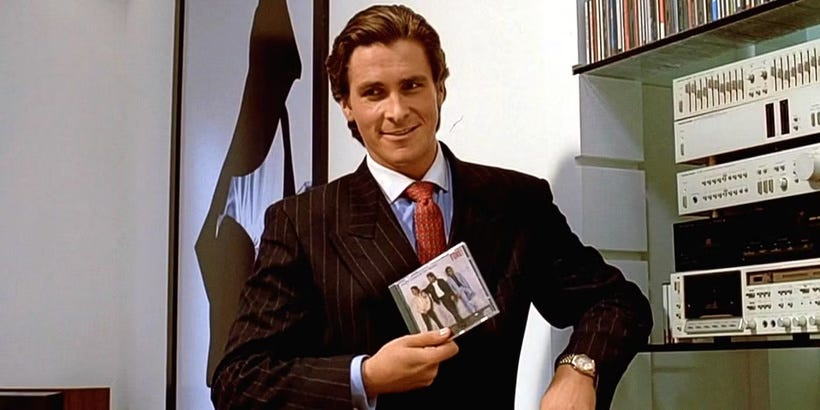

Nowhere is this more incisive than in the scenes where Bateman offers his deranged pop music exegeses. Huey Lewis and the News, Whitney Houston’s and, of course, Phil Collins. In one of many scenes that possess their own self-contained iconicity, he avails two disinterested sex workers with sincere musings on post-Collins Genesis and the life-affirming lyrics of In Too Deep.

This monologue becomes a prelude to one of the film’s most ridiculously funny, strange yet disturbing set pieces: a grotesquely performative threesome set to the insistent synth-pop energy of Sussudio. A Lacanian fever dream of masculine auto-eroticism unfolds, as the camera lingers on Bateman admiring himself in the mirror, having sex, ostensibly, with his own reflection.

Watching this now, in 2025, brings a strange sense of temporal disjunction. The film, for me, is locked in the turn-of-the-millennium critical moment, yet it's set in the 1980s, and now being revisited from the vantage point of my fifties. It skips across three distinct eras of my life, each viewing refracted through a different self.

Rewinding the Self

Because of my specific relationship with American Psycho, rewatching it inevitably prompted reflection on the shifting contexts through which I’ve engaged with the film, then and now. It brought to mind Barthes’ maxim from The Death of the Author: a text changes over time because we do.

What struck me this time was how the film’s tone manages to feel both dated and unnervingly prescient. It remains a perverse, nihilistically playful satire on masculinity. Still shocking in places, but unsettlingly in tune with contemporary debates around men, gender, and identity.

The film has rightly earned its place as a touchstone of turn-of-the-century cinema, though it never quite reached the pop-cultural saturation of Fight Club. Mary Harron, meanwhile, still doesn’t get the recognition she deserves for the precision with which she balances satire, horror, and irony. Perhaps it's because her depiction of masculine psychosis is so intricately embedded within the textures of consumer capitalism and media spectacle. Or maybe it’s because she’s a woman directing one of the most aggressively male-coded yet critical cinematic autopsies - a complex subversion that resists the usual reappropriation into social validated victimhood.

Watching it now, at 51, I felt attuned in a completely different way. Not because I discovered something new - though that’s always possible - but because I’m no longer the same viewer. When the film came out, I was 25 and just starting university.

It’s difficult to recall who I was then with any real clarity. Memory always risks becoming narrative, recomposed by the present, rewritten through the lens of who we've become. The echoes of my mid-20s self are filtered through the story I now tell about going to university and studying film. As a kid, my cinematic formation was limited very much to the mainstream. University expanded not just what I watched, but how I watched.

Reading critical theory in film studies gave me frameworks to (re)examine the films that had shaped my understanding of manhood. It was a period when I leaned hard into the discovery of intellectual possibility, realising ideas and ways of thinking existed that I’d never previously encountered. At the same time, those ideas challenged the familiar self I thought I knew. Through them, I came to understand masculinity not as biological destiny, but as a cultural construct: unstable, performed, and ideologically loaded.

Looking back now, it’s interesting to consider why American Psycho resonated with me as a subject of study. It would be disingenuous to say it was purely an intellectual alignment with its satire of patriarchy and capitalism. If I’m honest, it was more a mix of critical interrogation and seduction - Bateman’s embodiment struck a nerve, even as I tried to unpick the machinery behind it.

Perhaps it’s the cool detachment, the aesthetic control, the curated distance. Maybe it was the gloss of material culture, or the fact that the film walked a razor-thin line of acceptability - the kind of cultural object that made you feel edgy just for engaging with it. And then, of course, there’s Bale’s body itself: a contoured, cinematic ideal that, then as now, offers a blueprint for aspirational masculinity.

But how did I reconcile all the other stuff? The psychopathy, the alienation, the nauseating frat-boy banter, the probable schizophrenia? Of course, we critiqued it. Rigorously, even. Yet I recognise now that my engagement wasn’t purely critical. It wasn’t quite empathy or admiration, but certain elements of Bateman’s depiction felt, let’s say, homo-socially relevant. His performance of masculinity - controlled, aestheticised, hyper-competent - tapped into something I recognised, or perhaps aspired to, even as I denounced it.

Film has a unique capacity to activate cognitive dissonance—perhaps more than any other medium. Or more precisely, to engage what Freud called ambivalence: that core emotional dynamic where attraction and repulsion operate symbiotically.

It’s a question we recently discussed on The Cinematologists while exploring war films and the problem of implied glorification. American Psycho, like Fight Club, is a text that invites projection. As Stuart Hall would have it, it can be decoded in ways that reflect a viewer’s desires more than the film’s critique.

In that interpretive circuit, the viewer is the variable. What one brings to the film shapes what one takes from it.

And watching it now, I take something very different.

Bateman and his fraternity are - what’s the word - oh yes, douchebags. How can anyone now watch these characters without a cocktail of contempt, anger, and secondhand embarrassment? The idea that I might have once identified with them, even partially, now feels deeply uncomfortable.

The production design and materialist milieu once seemed aspirationally sleek; now they register as stilted, oppressive, and claustrophobic. The humour, which I used to find darkly ironic, feels instantly queasy.

Bateman himself is risible, pathetic, infantile. Beneath the lacquered surface, there’s no real character arc, the existential crisis is surface deep . The violence, while stylistically slick, is devoid of weight or consequence. It’s not an expression of inner torment; it’s choreography masquerading as meaning.

And yet, disturbingly, I can’t shake the sense that in today’s ecosystem of toxic male role models, Bateman is creeping back into relevance. Despite the ultraviolence and overt misogyny - or perhaps because of it - his stylisation has aged too well: the fetishised wealth, the sculpted physique, the designer armour. He fits, all too neatly, into the aspirational logic of the so-called “high-value male.”

Surface Tension

I dug out my dissertation to revisit my original reading of the film. There was nothing particularly earth-shattering in the analysis: Patrick Bateman as blank nihilist, a surface onto which the presumed male viewer could project. Surfaces dominate, mirrors, glass, and tiles that blur. The film’s visual logic aligns with cinematic representations of schizophrenia, dissociation, and the fragmented self.

I gave considerable space in my thesis to the now-iconic morning routine sequence. But looking back, there was probably more fascination than critique in my tone. It remains as close to a perfect character-introduction montage as cinema offers.

Rewatching it now, it struck me just how much just this scene alone aligns with current trends of masculine self-actualisation, which while not problematic in and of themselves have been somewhat weaponised in discourses of male reassertion, where discipline and aesthetics are framed as moral superiority.

Harron immediately immerses the viewer in the cognitive architecture of Bateman’s postmodern apartment: a sterile, surface-obsessed interior that “mirrors” his psychology, but also signals that he is rich, composed, and high-functioning. Bale’s detached voice-over calmly narrates his routine: crunches, lotions, masks. The soft piano score lends it all a meditative precision, bordering on reverence.

His body, tanned, sculpted, isn’t a site of raw strength, but of control. At the time, I wrote about how Bateman’s presentation veered toward a queer-coded aesthetic, though never explicitly enough to challenge the hetero-viewer’s capacity for projective identification. In the '90s, the image of the straight man obsessively grooming himself shifted from deviant to aspirational, narcissism rebranded as self-discipline.

And yet the sequence is undeniably homo- and auto-erotic. The camera lingers, caresses, indulges. But whose gaze is it? The viewer’s? Bateman’s? The culture’s?

I couldn’t help but smile again when he puts on the ice mask to eliminate puffiness around the eyes; it reads retrospectively not only as marker of Bateman’s extreme self-maintenance, but a knowing poke at the saturated iconography of mask-wearing superheroes.

Bateman’s obsession with not aging is another thread that now feels eerily prescient. What once played as darkly comic exaggeration now aligns disturbingly well with contemporary masculine ideals of self-optimisation. It made me think of tech entrepreneur Bryan Johnson, whose quest for biological immortality is chronicled in the recent documentary Don’t Die: The Man Who Wants to Live Forever. Johnson spends millions each year trying to reverse his biological age, tracking every micronutrient, breath, and bowel movement like a quantified Bateman (minus the bloodlust one assumes). Both figures are animated by the same pathology: the terror of decline, of softness, of mortality, and the fantasy that with enough control, money, and discipline, entropy itself can be held at bay.

Harron reflects this pathology not just in performance, but in composition. She frequently shoots Bale through glass, mirrors, and translucent surfaces, establishing a visual dialectic between narcissism and spectrality. Bateman’s image is everywhere, but his substance is nowhere, we’re not witnessing a diffusion of subjectivity so much as the hollowing out of presence altogether.

This visual strategy deepens the film’s central tension: man as polished surface, masculinity as disappearance into the symbolic.

Fascinatingly, if you look closely at the film’s opening tracking shot through Bateman’s hallway, you’ll catch a framed image of the Marlboro Man, the once-ubiquitous cowboy icon of American ruggedness and stoic virility. It’s a sly allusion to an earlier model of masculinity: grounded, mythic, tangible, even as it was equally constructed and ideologically fraught. That image now sits inert, a relic. Bateman’s version of manhood isn’t built on grit and dust, but on artifice, finance, and self-consciousness. A masculinity of projection and empty signification.

Bateman, while peeling off his exfoliating mask (a doubling of masks, literal and figurative), explains in chilling monotone:

There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me, only an entity, something illusory, and though I can hide my cold gaze and you can shake my hand and feel fresh, gripping yours, and maybe you can even sense our lifestyles are probably comparable, I simply am not there.

Bateman’s monologue is the apex of postmodern masculine alienation. His meticulously maintained exterior conceals not depth, but void - he isn’t hiding his true self; he’s revealing that there’s nothing there to hide.

This scene - probably the most cited alongside the infamous business card sequence- now reads less like biting satire and more like high-concept parody. Especially when refracted through today’s productivity-obsessed culture, where morning routines, self-optimisation, and aesthetic curation have become a form of lifestyle branding.

I described American Psycho as embodying a kind of masculine ambivalence. A paradox in which masculinity is both hyper-visible and utterly hollow. Bateman’s persona is a meticulously constructed shell. The film skewers the idea of a coherent male subject, yet paradoxically re-centres him - even if only to portray the void.

American Psycho reads a clear deconstruction the gravitational pull of white male power caught between the contradiction of the old and new man. Yet its critiques hyper-masculinity’s hollowness still contain the fetishisation Bateman’s body, lifestyle, and affective detachment. He is rendered with clinical precision, framed, lit, and edited like a Calvin Klein ad for nihilism.

Watching the film now, with the shadow of the modern “manosphere” looming large, Bateman’s morning routine feels eerily prophetic. The obsession with discipline, aesthetic perfection, and emotional repression echoes the rhetoric of today’s alpha-male influencers - who treat self-regulation as both virtue and weapon.

What once passed as satire now mirrors the exact vocabulary of a subculture obsessed with becoming a “high-value man.” The ice mask, the sculpted abs, the encyclopaedic knowledge of products and protocols - lifted directly, it seems, from a from a YouTube tutorial.

Case in point: see below, where fitness influencer Will Tennyson mimics Bateman’s routine. He leans into the parody to undercut the psychopathy, sure , but beneath the irony lies a clear homage to the seductive logic of Bateman as signifier.

That American Psycho was intended as a parody only makes its unintended legacy more disturbing. Bateman becomes aspirational not despite his detachment and misogyny, but because of them. The film’s critique is clear, but the cultural uptake reveals just how potent the fantasy of control remains.

In the post-Mad Men era, Bateman reads like Don Draper’s spiritual successor—minus the charm and tortured introspection. His secretary isn’t a colleague or confidante; she’s a status symbol. Every woman in Bateman’s world serves a function: arm candy for business dinners, a vessel for sex, or ambient scenery to offset his performance of success. It’s a fantasy of female complicity, where the ideal partner is mute, compliant, and conveniently absent when not required.

Today’s “high-value male” rhetoric echoes this vision with unsettling precision. In the manosphere, women are framed as exclusively attracted to power, wealth, and dominance. The memes say it all: “looking for a guy in finance,” “6-figure salary, 6-pack abs, 6 feet tall.” These aren’t satirical—they canonise Bateman. They don’t mock him; they market him.

When Bateman murders a homeless man—psychopathy, delusion, both?—it’s also framed ideologically. “Why don’t you get a job?” he sneers, revealing a worldview in which poverty is a moral failing. In both Bateman’s world and today’s manosphere echo chambers, success is always self-made. Circumstance is just an excuse for the weak.

Then there’s the paranoia, the creeping sense that unseen forces are undermining him. Society, women, family, the law: some ever-present ‘Big Other’ conspiring against male autonomy. In this light, Bateman anticipates the rise of the so-called “sigma male”, a label now used to signal men who reject traditional hierarchies. Detached, mysterious, ungovernable: not an alpha, but something darker, more elusive. A self-contained ecosystem of aesthetics, control, and violence. Not a monster, but a misunderstood genius. That we now have an entire vocabulary - sigma, high-value, lone wolf - only reinforces how far Bateman’s image has travelled. Not from critique to cautionary tale, but from satire to aspirational blueprint.

Brad Eposito, writing in Vice in 2022, discusses Batmen memes that started popping up on Tik Tok. He argues rightly that the text, symbolic laden with pop culture references, along with the stylised mannerisms of dialogue rich for lip-synching had prenniallially reemerged on the internet.

To a generation of men online, American Psycho was more than a satirical take on excess – it was a bible for true development. And now, as a fresh audience tackles the character with an arsenal of new platforms and groupthink, Bateman’s illusory gaze is everywhere.

And just the other day this image popped up on my feed:

It’s been 25 years since Harron’s adaptation landed like a needle in the postmodern bloodstream. But, Patrick Bateman clearly still possesses the symbolic iconic value for another iteration of appropriations and applications.

Meaning in the Circuit

How we interpret films is shaped by a kind of circuit: what the film makes available through form, tone, and narrative; our own psychological and social subjectivity; and the wider cultural context; the norms, values, and discourses that guide interpretation.

In this sense, American Psycho belongs to a pantheon of films “allegedly” misread by a generation of male viewers with an irony bypass. The Matrix is another obvious example, with its now-infamous red pill/blue pill scene in which Neo (Keanu Reeves) is offered the film’s core philosophical choice: embrace an uncomfortable truth or remain blissfully ignorant.

The directors, Lana and Lilly Wachowski, have since spoken of The Matrix as a trans allegory. It’s fascinating, then, to see how the phrase “taking the red pill” has become cultural shorthand among certain online communities. Not for awakening to gender fluidity, but as a metaphor for rejecting feminism and so-called “woke” ideology. The allegory is there, but the meaning is...reallocated.

Here’s the rub: if Barthes’ “death of the author” has any validity, then these aren’t “misreadings”. They are part of the interpretive circuit. The films become feedback mechanisms for alienation, grievance, and - perhaps more compassionately - genuine confusion among young men presented with increasingly contradictory ideals of masculinity.

“Toxic masculinity” is today, locked in conceptual battle with more progressive notions of male being. Men are urged to be emotionally literate, self-aware, vulnerable and yet simultaneously strong, stoic, and self-contained.

Within cinema, those contradictions persist. Masculinity remains a riddle. Still unresolved. Perpetually in crisis. And perhaps, in cinema’s repeated attempts to critique or reconfigure it, we find that its contradictions are not only persistent, but foundational. The more things change, the more they seem to stay the same.

We Still Love Watching Us Fall Apart

Rewatching American Psycho brought with it an odd sense of gratitude, relief, even, that I’m no longer in my twenties, trying to shape a sense of self within today’s culture. The 1980s and ’90s were far from a utopia of progressive values, but at least the cultural battle lines felt clearly drawn. Today, the terrain is more fluid, but also more disorienting.

In some ways, there’s greater agency now to define identity on one’s own terms. But the frameworks through which that identity is constructed, particularly for young men, are increasingly dictated by algorithmic feedback, influencer psychology, and masculinities shaped by rage-bait polemics. Film, once a relatively stable cultural medium through which identity and ideology could be projected, challenged, and reflected upon, has lost much of its centrality. The internet, for all its promise of pluralism and democratisation, is a far more chaotic, tribal, and unforgiving space in which to build a coherent subjectivity.

If American Psycho gave us a man who couldn’t feel, couldn’t connect, and ultimately couldn’t distinguish himself from the gleaming surfaces he inhabited, then today’s cinema still circles that same existential drain. The men on screen are often still trying - often failing - to reassemble the self from its fragments of past ideals.

We’ve added new vocabularies: trauma, toxicity, vulnerability, care. But the narrative engine remains eerily familiar. Men are still central. Still fractured. Still wandering a symbolic terrain shaped by a world that no longer guarantees them anything, socially, economically, or emotionally.

I thought of so many films that owe a debt to American Psycho—some thematically, some formally, some both. I won’t go into detail here, but among them: Shame (2011), The Big Short (2015), You Were Never Really Here (2017), The Card Counter (2021) (or really anything from late-period Schrader), The Power of the Dog (2021), and Beau is Afraid (2023).

So the question that lingers for me, beyond the familiar refrains of “what is masculinity?”, “how do we counteract misogyny?”, “how are we raising boys?”, or even “what does an acceptable masculinity look like today?”, is this:

Why do we still love watching men fall apart?

Below for paid subscribers. I ummed and ahhed about what to focus on as a follow up to these piece on American Psycho. I want to write more pieces on masculinity and cinema in the coming weeks/months, but I thought it might be interesting a rundown of films focusing on male protagonists/heroes that have changed over time, because I’ve changed. So that’s the extra for this post.

Thanks so much for reading and watching, your support really humbles me. Though we’re constantly told to find passion and purpose from within (which I agree with), building an Substack community to explore the excitement and confusion has been a crucial support over the last year.

I’d really appreciate if you can restack/share to your networks. This is a gesture of curatorial practice and a small act of resistance the algorithmic overlords.

If you’re not already a subscriber, please consider doing so by hitting the button below.

Subscribed

A paid subscription is £3.50 per month and you will get access to the full articles and podcasts I produce. There is a lot of work that going into the writing and podcasting, so becoming a subscriber is the best way to support the continuation of the work.

I’ll also send you and physical postcard, wherever you may reside, how can one resist:

If you don’t want to subscribe but could see your way offering a small tip the labour of producing the work, hit the button below.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Contrawise to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.